Allows Utilities to Maintain Dominance in Markets

Frank Lacey has worked in competitive energy markets since their inception as a consultant to utilities navigating restructuring and as a direct market participant once the markets opened. After more than twenty years in the industry, he launched Electric Advisors Consulting, in the fall of 2015. His focus is assisting clients with energy market issues — regulatory, strategic and business. His clients include energy market participants and end-use consumers. He can be reached at frank@eacpower.com.

Default service prices have been wrong for two decades.

Most of the states that have implemented competition in electric and gas sales have employed a Provider of Last Resort, POLR, or default service to supply electricity to customers who do not select an alternative provider. Yet the utilities allocate few to no "costs to serve customers" to default service rates.

This practice has allowed the incumbent utilities to price default service below market rates. And it has allowed them to maintain unregulated monopoly-like power and dominant market positions in the energy markets in their respective service territories.

The failure to allocate costs appropriately to a utility business unit is in direct conflict with cost allocation guidance from the National Association of Regulatory Utility Commissioners, NARUC. Until the default service pricing distortion is corrected, utility default service providers will continue to hold an anti-competitive pricing advantage in the provision of retail electricity service.1 Regulators should act to correct this major market flaw.

Default Service Rates Artificially Low

Several states have deregulated or restructured their energy markets to allow consumers to choose their own electric and or gas supplier. With few notable exceptions, the deregulation models adopted in these states called for the incumbent utility to become the POLR or default service provider.2

While initially envisioned to serve a small number of customers who needed a "last resort" provider, the market rules incorporated into most restructured markets placed all customers on last resort service at the inception of retail competition, making it more of a "default" service.

Because an appropriate amount of costs are not allocated to default service, customers are reluctant to leave their incumbent utility. They are receiving electricity that is subsidized by distribution rates.

The default service pricing subsidy provides the incumbent utilities with what are effectively unregulated monopolies. Default service customers are not being charged an amount that is reflective of the cost to serve them.

The lack of any meaningful cost allocations to default service allows (requires) the incumbent utilities in restructured states to understate the price of retail electricity. This practice effectively eliminates competitive suppliers from functioning in those markets.

This pricing error leads to numerous market flaws. Distribution rates are too high. Default service rates are too low. Customers are receiving incorrect and inappropriate price signals from their host utilities.

Customers who have switched to competitive suppliers are subsidizing those who stay on default service. And competitive suppliers are at a distinct pricing disadvantage compared to default service providers, allowing the utility market power to proliferate in retail energy markets.

This pricing incongruity allows utilities to maintain a stronghold over customers in their service territory. It also has given rise to claims about overcharging by competitive suppliers.

Freestanding Default Service Business Couldn't Survive

It is easy to prove the anti-competitive pricing in default service. One only needs to contemplate how long a default service business could operate if it was removed from the distribution company but kept its current cost structure intact. The short answer is that it would survive for only a very short period of time - technically, not even a day.

Default service companies need to issue tens of thousands of invoices every day and then need to process revenues as they come in. But because no costs to serve customers are allocated to default service businesses, there would be no money to pay any employees to perform those functions, nor any other function involved in running a default service business.

The current default service businesses would be bankrupt in a matter of days, or even hours, if they were operated outside of the distribution utilities. Clearly, this is a fundamentally flawed system and one that conflicts with all traditional rate-making standards.

Cost allocation is a fundamental tenet of utility ratemaking. The principles of cost allocation are fully endorsed by NARUC and should be applied to default service as they are to all other utility rates.

Allocations are required to appropriately assign fixed costs to multiple products or services that drive the costs. The principles of cost allocation are the foundation for nearly every (if not every) utility rate, aside from default service rates.

The NARUC Cost Accounting Manual states:

"While opinions vary on the appropriate methodologies to be used to perform cost studies, few analysts seriously question the standard that service should be provided at cost. Non-cost concepts and principles often modify the cost of service standard, but it remains the primary criterion for the reasonableness of rates. The cost principle applies not only to the overall level of rates, but to the rates set for individual services, classes of customers, and segments of the utility's business." Emphasis added.

NARUC has separately published cost allocation principles. The principles should be applied, according to NARUC "whenever products or services are provided between a regulated utility and its non-regulated affiliate or division." NARUC principles apply to default service, a business segment where many services are provided by the distribution company:

"The allocation methods should apply to the regulated entity's affiliates in order to prevent subsidization from and ensure equitable cost sharing among the regulated entity and its affiliates, and vice versa." Emphasis added.

NARUC states that the objective of its guidelines is to "lessen the possibility of subsidization in order to protect monopoly ratepayers and to help establish and preserve competition in the electric generation and the electric and gas supply markets." Emphasis added.

In fact, to ensure the competitiveness of markets, NARUC states that generally, "the price for services, products and the use of assets provided by a regulated entity to its non-regulated affiliates should be at the higher of fully allocated costs or prevailing market prices." Emphasis added.

NARUC's objectives and guidelines have been ignored in pricing default service.

Market Distortions

The default service pricing anomaly has given rise to many market distortions and has resulted in competitive suppliers being cast in a negative light in many jurisdictions. It has caused competitive suppliers to spend millions of dollars in unnecessary marketing costs, regulatory costs and legal and compliance costs.

Most important, it has resulted in customer harm from being constrained to the utilities'"no service" products and from the lack of product options that are available in more competitive markets.

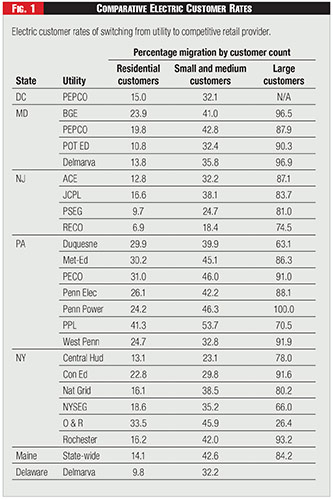

Table One details the percentage of customers who have chosen a competitive electric supplier across many of the deregulated electricity markets. Despite two decades of competition and dozens of suppliers vying for customers in every market, the incumbent utility stronghold on the market, especially over residential customers, is painfully clear.

See Figure One.

At the low end, we see single digit migration rates for residential customers to competitive suppliers. The Pennsylvania market shows the most promising residential migration numbers — ranging from the mid-twenty percent range to just over forty percent in PPL's service territory.

States that have deployed municipal aggregations to facilitate customer migration are not included in this chart because aggregations are simply a regulatory fix that masks the pricing problem in the short-term. Municipal aggregations do not solve the pricing problems over time.

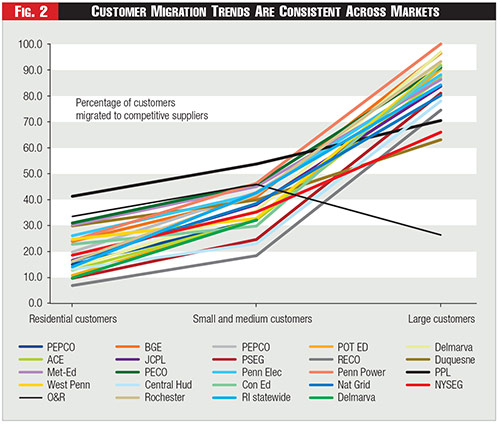

Figure Two shows the same data in graphical form. The utilities all show the same migration trends. Small customers do not migrate away from the utilities while the largest customers participate in the competitive markets at very high penetration levels.3 See Figure Two.

Artificially Low Default Service Prices Harms Customers

Under an appropriate cost allocation approach, the customers will pay, on net, the same amount every year. Cost allocation does not cause an increase in costs to customers. It only moves costs to different buckets.

Because there is no total cost increase to customers with an appropriate cost allocation, the argument that the customers are better off under the current pricing model is flawed. In fact, because of the inaccurate pricing signal with the current model, customers are harmed in meaningful ways.

Most important, customers are not receiving the appropriate price signal for energy. This results in a potential to over-consume energy provided by default service providers, yielding what could be a higher overall monthly cost to the customer than would otherwise incur if the electricity was priced appropriately.

The distribution subsidy also creates a barrier to evaluating competitive offers. It is impossible for customers to assess fairly a competitive offer when the utility price is artificially low.4 Because the basic competitive market product would be viewed as uneconomic by the consumers, competitive suppliers are less likely to invest fully in the market, depriving customers of other products and services that the suppliers might be inclined to offer in that market. Foregone products and services include many that might reduce a consumer's consumption overall, benefitting the customers and the environment.

Finally, the distribution subsidy results in a distribution rate that is too high. Customers who have moved away from the utility are forced to pay costs that benefit customers who remain on default service.

Recent Analyses Reveal Subsidies

Substantial analyses seeking to understand the magnitude of the distribution subsidy have been performed in two recent distribution rate cases. The results of those analyses have been presented to utility commissions in Pennsylvania and New Jersey in the form of expert testimony in those respective cases. These analyses show that the subsidy is significant — a penny or more per kilowatt-hour — as high as fifteen percent of the default service rate.

In PECO's rate proceeding, Pennsylvania Public Utility Commission's docket R-2018-3000164, NRG Energy Company provided an analysis of PECO's distribution rates to determine if any distribution costs were being used to subsidize PECO's default service rates. The analysis showed that the subsidy of PECO's default service by PECO's distribution business amounts to 1.25 cents per kilowatt-hour for residential customers.

If that amount was properly allocated to PECO's default service rates, it would increase those rates by approximately fifteen percent. Of course, if the costs were properly allocated to default service, the corresponding cost components from the distribution rates would decrease by the same amount.

In PSEG's rate proceeding, New Jersey Board of Public Utilities docket ER18010029, I undertook on behalf of Direct Energy, a similar analysis. My analysis showed that the subsidy that PSEG distribution rates were providing to PSEG's default service amounts to 1.0 cents per kilowatt-hour to residential customers. Because PSEG's default service rates are higher than PECO's, an additional 1.0 cents per kWh represents a subsidy of about eight percent to residential default service rates.

In the PSEG rate case, not enough information was provided by the utility to determine the magnitude of costs (working capital, credit, bad debt, etc.) that should be directly assigned to default service. As a matter of conservatism in my analysis, I assumed that those should be only partially allocated.

If direct costs were assigned properly to default service and indirect costs were allocated appropriately, the actual costs to serve default service customers in New Jersey could be in the range of 1.5 cents per kilowatt-hour.

With default service rates ranging from the low single digits to the low teens in cents per kilowatt-hour in markets across the country, and the unallocated funds (or subsidies) ranging from 1.0 to 1.5 cents per kilowatt-hour, this subsidy can be valued anywhere between eight percent and fifty percent of a monthly default service charge. A subsidy of that magnitude, or that scale of utility "discount" severely distorts the market, unfairly advantages the utilities over competitive service providers and harms customers.

Conclusion

Appropriately allocating costs currently paid by distribution customers to default service is a critical next step in creating more competitively neutral energy markets in the United States. This one step will not create the perfect markets, but it will remove a significant anti-competitive pricing advantage held by monopoly utilities.

It will also remove a subsidy that competitive supply customers are forced to pay to benefit default service customers, and it will help create a market that competitive suppliers are more willing to invest in. At the same time, if implemented correctly, it keeps distribution utilities financially whole. It is a win-win-win solution benefitting all market participants.

Endnotes:

1. While this article is focused on electricity markets, the same pricing problems exist in gas markets. The costs to serve customers are not allocated to those customers' rates. Instead, they are charged to distribution customers.

2. Most of the deregulation models deployed in the U.S. are generally very similar. In contrast, Texas electricity customers and Georgia natural gas customers were placed with market participants at the inception of those markets and default service in those markets is truly a "last resort" service, not a "default" or "do nothing" service.

3. The one anomaly revealed in this chart is in the Orange & Rockland Utility in New York. It shows an uncharacteristic low level of customer migration at the large end of the customer spectrum. It is not clear whether this is a data error on the NY PSC website, or if there is a market anomaly in that market that results in the largest customers remaining with the utility.

4. Under no circumstance should any price, including the utilities' default service price, be considered a benchmark price. The default service price is for a specific product with a specific set of parameters associated with it. Additionally, as this article notes, it is heavily subsidized. It comes with a certain level of service and a limited ability for it to be modified in any way to meet customers' needs. Regardless, regulators in many states have mandated rules that require a comparison of all products to the utility default service price. These requirements include for example, a requirement that the default service price be placed on a customer's invoice, even if the customer is being served by another supplier, with a different product. Some have required that all sales interactions include a notice of the utilities' default service price.

Category (Actual):

Department: