Key Enabler of Renewable Energy Resources Integration

Ahmad Faruqui is a principal with The Brattle Group. He is an energy economist whose career has been devoted to pricing innovations. He has designed and evaluated a variety of pricing experiments in the U.S. and abroad and maintains a global database of more than three hundred tests of time-varying rates. Faruqui has testified on rate-related issues in several jurisdictions and presents frequently on tariff reforms.

Lea Grausz, an associate with Brattle, has experience in rate design and incentive-based ratemaking for electricity and natural gas. She has managed several rate design projects throughout the U.S., and in several provinces in Canada. She has also managed many other projects related to utility regulatory incentives, consumer response, and deployment of smart technologies. Previously, Grausz worked for four years for GDF SUEZ (Engie) in Paris where she led the economic analysis for price negotiations and contract arbitrations in long-term gas supply contracts.

Cecile Bourbonnais is a research analyst with Brattle, where she supports utilities and energy companies across North America on rate design, resource planning, ratemaking methodology, and business risk.

Clik here to view.

Clik here to view.

Clik here to view.

Clik here to view.

Clik here to view.

Clik here to view.

Clik here to view.

There is widespread agreement in the industry. Today's residential rate designs have outlived their usefulness and need to be modernized to meet the challenges of integrating renewable energy resources into the grid. There is also general agreement on what constitutes a modern rate design. Examples include cost-reflective rate designs such as time-of-use rate and dynamic pricing coupled with demand charges.

However, there are several reasons why the transition to modern rate designs has yet to be deployed to scale.Those reasons are discussed in this article along with proposed solutions.

Smart meter deployments now encompass half of the residential customer population in the United States, removing a major barrier to the modernization of rate designs. Smart technologies continue to proliferate in customer premises, including smart thermostats and appliances, high-efficiency air conditioners and heat pumps, battery storage, and smart phones.

The Internet of Things has arrived. With it a new generation of customers is born, customers who want better control over their energy use, who are avid for data, who want to have a minimum impact on the climate of the planet, and are willing to pay extra to do so.

A significant opportunity resides in these consumer trends as state governments set aggressive goals for their renewable portfolio standards. Including Hawaii and California with a goal of being one hundred percent renewable by 2045.

Dynamic pricing has the ability to modify consumer load shape, influence customer investment decisions, and facilitate the penetration of renewables. Customer interest, technology availability, and the widely-connected space we live in can only help. See Figure One.

Customers are encountering modern pricing designs in all walks of life. Airlines, hotels, car rentals, movie theaters, opera houses, sports venues, freeways and even parking lots are increasingly deploying dynamic pricing. At the same time, certain industries are using subscription plans, such as cell phones, Amazon Prime, Costco and Netflix.

Similar progress is yet to be seen when it comes to rate design for electricity. The reasons all revolve around three widely-held misperceptions. The most common misperception is that customers don't spend more than eight minutes a year focusing on their energy bill.

The second misperception is that modern rate designs will be too complex for customers to understand. And the third misperception, which is by far the most strongly held, is that modern rate designs will cause some customers to instantly see higher bills, causing them to complain loudly. Once their complaints get picked up by the media, this will lead to a major customer backlash.

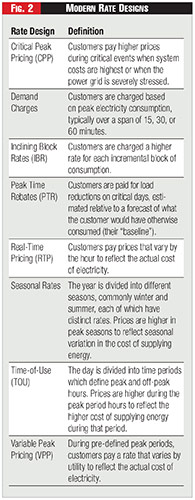

We lay out some thoughts on how to make the transition from today's tariffs, which are largely volumetric in nature and date back to the beginnings of the industry in the late nineteenth century, to modern rate designs. Modern rate designs come in many shapes and sizes. Figure Two provides a summary.

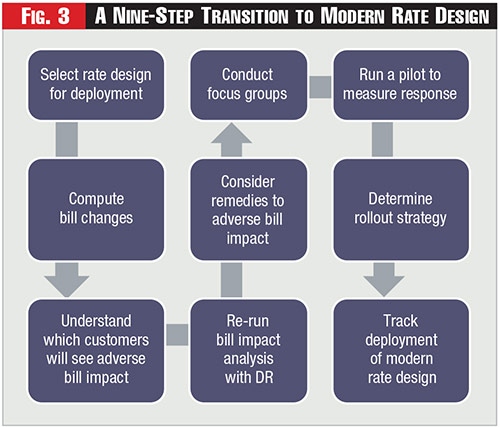

One pathway for modernizing rate designs involving nine steps is laid out in Figure Three.

First, pick the specific rate design for deployment, such as a higher fixed charge, a demand charge, and a time-of-use energy charge. In some cases, more than one rate design may be picked for deployment.

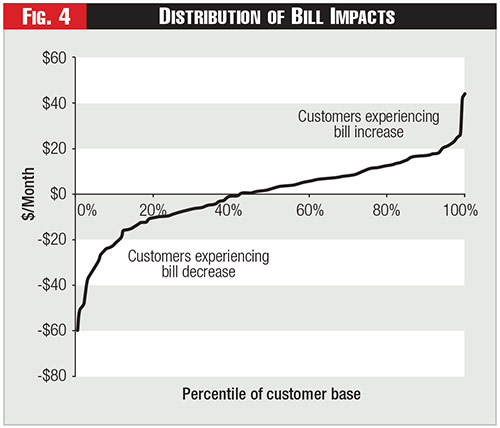

Second, for the chosen rate design or designs, compute bill changes for a representative sample of customers. Plot the results in the form of a propeller chart, such as Figure Four, identifying those who are going to see higher bills and those who will see lower bills.

Third, try to understand the socio-demographic and regional characteristics of those who are going to experience significantly higher bills. Use various pricing tools - such as creating a low-income customer class, offering rebates to selected customers - to mitigate the impact on vulnerable customers.

Fourth, re-run the bill impact analysis by allowing for a certain amount of demand response, using estimates from a model such as PRISM, the Price Response Impact Simulation Model, which forecasts peak load reductions under new rates. The adverse bill impacts should be lower than they were without demand response.

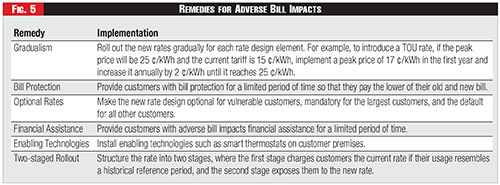

Fifth, if the adverse bill impacts are still significant for a certain group of customers, consider instituting one of these remedies shown in Figure Five.

Sixth, conduct focus groups with customers to communicate the rationale behind the selected rates and to see if they would be comfortable with the modern rate designs. Make appropriate modifications in language - and possibly in the rate design parameters, such as the magnitude of the fixed charge, the demand charge, and the charges for energy by time-of-use, as well as the duration and temporal location of the peak period - to make the modern rate designs understandable to customers.

Seventh, run a pilot to measure the amount of demand response. It should be designed on scientific principles that would preserve the internal and external validity of the results, allowing them to be extrapolated to the population of customers. Randomized controls, randomized encouragement, and matching controls are different ways of preserving pilot validity.

Eighth, decide on the rollout strategy. One can study the following examples of success:

Three utilities in Maryland - Pepco, Delmarva Power, and Baltimore Gas and Electric - have rolled out dynamic peak-time rebates as the default tariff to all their customers. Upward of eighty percent of customers have availed themselves of the rate and are saving money on their energy bills.

Arizona has a long history with time-of-use rates. These are offered on an opt-in basis by Arizona Public Service and the Salt River Project. Approximately fifty-seven percent of APS's residential customers and thirty-six percent of SRP's residential customers take service on a time-of-use rate. Of the fifty-seven percent of APS customers on a time-of-use rate, twenty percent are also on a demand charge. At SRP, customers across all customer classes on a time-of-use rate account for fifty-one percent of the energy consumed in the system.

Oklahoma Gas and Electric Company rolled out a sophisticated dynamic pricing rate, Smart Hours, to its residential customers on an opt-in basis a few years ago. The company also provided its customers the option to install smart thermostats through the program. A fifth of the customers have signed onto the rate and are saving significantly on their electric bills.

California's three investor-owned utilities rolled out mandatory time-of-use rates in 2016 for all residential solar customers, defining off-peak hours in the middle of the day to coincide with peak solar generation output. These rates sparked the adoption of solar-plus-battery systems in the residential sector. Sunrun, an industry leader, reports that more than twenty-five percent of its solar sales in California in the third quarter of 2018 included battery storage.

Fort Collins, a municipal utility located in Colorado, moved all its residential customers in October 2018 from an inclining-block rate to time-of-use energy rates, which come in two variations. One is for gas-heated homes. One is for all-electric homes. The deployment is mandatory.

In the same month, Sacramento Municipal Utilities District has begun rolling out time-of-use energy rates along with a twenty dollars a month service charge on a default basis in California. Details are shown in the sidebar to this article.

In Illinois, about fifty thousand residential customers of Commonwealth Edison and Ameren Illinois are on an opt-in real-time pricing rate.

Many states are considering whether to move their distributed generation customers into a separate rate class. Kansas and Idaho have agreed to make such a move. In Kansas, the Commission has approved a three-part rate for distributed generation customers.

In Ontario, Canada, time-of-use rates have been rolled out as the default tariff for energy supply to residential and small commercial customers since 2007. About ninety percent of these customers are on such rates, while the remainder are taking competitive supply from retailers. The distribution tariff in Ontario is a flat bill.

In Spain, the default tariff is a pass-through of hourly wholesale prices. It's estimated that about half of the customers are on the default rate. Residential customers in Spain also pay a charge for being connected to the grid, expressed as a per installed kilovolt amperes or kilowatt charge, similar in concept to what is in place in France and Italy.

In France, about half of the residential customers are on a time-of-use rate. This opt-in rate was created more than fifty years ago using interval meters.

In Hong Kong, CLP Power Limited has rolled out dynamic peak-time rebates to some twenty-seven thousand customers.

And, ninth, track the deployment of the modern rate designs, survey customers for feedback, set up social media sites and monitor the conversation, and make necessary modifications in the rate design on a regular basis.

Conclusions

With the installation of smart meters to half of the residential customers in the United States, and with the rapid emergence of new customer technologies, such as smart thermostats, digital appliances, rooftop solar panels and electric vehicles, the time has come for electric utilities to begin modernizing their century-old rate designs.

There are several ways in which to make the transition, and many jurisdictions have successfully made the transition using one or more of these methods. Utilities that have not begun to make the transition can study the lessons learned from these deployments and begin their own journey.

Category (Actual):

Department:

Clik here to view.