Why a risk-hedging product for small customers isn’t the gamble you may think.

Michael O’Sheasy retired in May from his position as product design manager for Georgia Power Co. to pursue a consulting career as vice president with Christensen Associates, Madison, Wis. O’Sheasy has 20 years’ experience in the electric industry as a costing and pricing expert witness and an innovator with such pricing products as real-time pricing, multiple load management and price-protection products. Contact him at MTOsheasy@lrca.com.

Mike Becker recently left Georgia Power, where he was a senior pricing analyst, to become a pricing manager with BellSouth. Prior to his work at Georgia Power, Becker was a pricing analyst for Conrail in Philadelphia. In addition to the design of Flat Bill, Becker was instrumental in developing another innovation called the Interruptible Exchange Service. He may be reached at Mike.Becker@BellSouth.com.

Flat pricing. Many small electric service customers want it, many electric companies do not think they can provide it. That creates a market opportunity for a convenient, flat electric bill.

We are not talking about flat rates per kilowatt-hour, nor about a budget bill program. These common products help customers to levelize monthly bill variance, but do not actually protect customers from price and billing risk. To “protect” means to shelter from risk and uncertainty. The difference between levelizing and actually protecting the customer is where the gap lies—and where a company can step in and capitalize.

What many small customers really want is a pure “flat bill.” A flat bill is a fixed annual bill that provides 12 months of equal payments with no year-end settlement. It can even be one annual bill. A flat bill also offers absolute predictability because it protects against any volatility in weather, behavior and energy costs for a specified period of time. In other words, the flat bill insures customers against the risk of increases in cost and quantity purchased.

This flat bill concept is not rocket science. It is not even considered innovative. It is, however, the pricing strategy of choice in many industries, including some that are similar to the electric industry. First, there is the capacity-constrained Internet service sector, which quickly transformed from volumetric pricing to flat bills. Then there is the cellular phone service market, which has evolved from pure volumetric pricing to a more customized menu of flat offerings. Even the volatile retail gas market has been experimenting with its version of residential flat bills.

Not to be outdone, some innovators in the electric industry recently began offering financial hedging products that absorb risk from large customers. Why not offer this kind of protection to customers with small electric loads?

It may sound absurd. Sure, you might say, it’s fine for other industries, but not for the complex and dynamic electric industry. System capacity would become inefficient and unmanageable; peak loads would skyrocket, requiring new investments in existing plants; or it might even damage system reliability. Customers won’t pay for it. The absorbed financial risk would be too great. Regulators won’t approve it.

If that’s your reaction, you are not alone. These are what we consider the “norms” or “the box.” To think outside of this barrier, we have to define each of these norms and then challenge them.

Quashing the Misperceptions

Challenging the norms is the strategy we adopted at Georgia Power in pursuing a flat bill option for our small customers. The result was a flat bill pilot program rolled out June 1, 2000, and involving 500 residential and small business customers. The goal of the program was to understand the myths about the mysterious “flat bill.”

To begin with, we examined the potential hurdles and were surprised to discover that there were few. On the surface, the idea of a pure flat bill in the electric market is frightening, posing potential threats in terms of capacity constraints, the price premium, revenue risk and regulations. But when we challenged these norms through market research, load shape modeling and product testing, we found an exciting new pricing opportunity. Let’s examine each of these perceived threats and the realities we came to understand.

Norm 1: System Capacity Will Suffer. The primary reason flat bills are uncommon in our industry is the fear that customers will change their behavior, leading to a dramatic increase in their load demand. Although this worry is a norm, we have been unable to find quantitative research to support it.

We used a three-prong approach to challenge this belief. First, customers were surveyed to learn how they would behave on such a pure flat program. Then those results were applied to a modeling program that analyzed and projected the impact of these customers’ behavior change on their load shape. Finally, we conducted a pilot that metered the participants’ actual energy and peak consumption. This information was normalized to account for weather and compared to the previously measured behavior for these customers. The results were measured empirically using test and control groups.

Reality Check. We found that there was an increase in both energy and demand consumption. However, the impact was minimal; better yet, it occurred mostly during off-peak periods. That can be explained by the fact that most of the growth was the result of customers lowering their thermostat setting during the summer months. The effect of this action was minimal during peak hours because the electric cooling system was running full speed regardless of whether the thermostat was set at 76 degrees or lowered to 74 degrees. But during the off-peak times, when the weather had cooled, the threshold of the thermostat setting had a greater impact on the running time of the cooling system.

Though we found a minimal increase in energy consumption, we believe the program can be energy-efficient. This program is the only one for residential customers that can accurately measure participants’ change in behavior in terms of the financial impact on their annual bills. Typical volumetric pricing used by weather-sensitive residential or small business customers reveals a change in behavior from month to month, or month to the same month of the previous year, but that is less accurate, since weather conditions will always blur the results. Because a flat bill is based on weather-normalized behavior, any change in demand will be accurately quantified in the customers’ next year flat bill offer. In addition, improved efficiency will be rewarded by a lower offer regardless of the weather. If the program is marketed correctly to inform customers of how they could be more efficient and how the program can measure and reward them, it could provide the means for customers to become more energy-efficient.

Norm 2: Customers Won’t Pay For It. The commonly held belief is that electricity is a true commodity and consumers will always choose the lowest-cost option. But flat bills should not be the cheapest pricing package for the customer in the long run due to the significant cost and quantity risk the programs place on energy retailers. It is hard to argue this point when simply looking at marketing factors such as price, place and promotion. But what about the fourth element of the marketing mix, the package?

We wanted to learn if customers would recognize the value of an electric service package that provides convenience and “peace of mind,” and if so, would they be willing to pay a premium for it? To test this issue, we researched the price sensitivity of residential customers through a survey. As mentioned, we also launched a pilot program and surveyed actual participants.

Reality Check. The survey results showed that many customers valued predictability and convenience and were willing to pay a premium in their electric bill. The results were run through an optimization model to determine how the premium would provide the optimal financial impact for the energy company. Because our previous market research predicted that pilot participants would use more energy, the forecasted additional energy was built into the price of the flat bill offer.

Public interest in the pilot program far exceeded our expectations. The day after the pilot was filed, news of it made the front page of the Atlanta Journal-Constitution’s business section. Soon, it was reported favorably on both national radio and television—all for a 500-customer pilot, which hadn’t even mailed promotions about the product yet. It certainly confirmed our research that there was a need in the market. Later, the high penetration rate gained from the mailed offers indicated that the customers purchased the flat bill to meet their budgeting needs. In a follow-up survey of pilot participants, 95 percent reported that the flat bill either exceeded or met their expectations.

Norm 3:Risk Would Be Unmanageable. Risk is frightening, and it exists everywhere. But risk is transferable. Here the financial risk can be deflected from the customer to the supplier, Georgia Power.

We wanted to see if this risk could be dissected and managed. The major risk is the weather impact. If the summer is hotter than normal and the winter is colder than normal, the result is that the amount collected from the flat bill would be less than the bill amount otherwise paid by the customer. Conversely, if mild weather occurs, then the amount collected by the flat bill would be greater than the amount otherwise paid by the customer.

In some industries this risk might not be manageable; however, in the electric industry it acts as a natural hedge. In hot weather years, when the flat bill is under-recovering, the company is generating unusually high returns from its other weather-sensitive customers not on the flat bill. In mild weather years, at the same time the flat bill is over-recovering, the company is generating unusually low returns from its other weather-sensitive customers. Some energy companies in the industry even purchase weather insurance, a hedge the flat bill program provides for free.

Another financial risk is the change in individual customer behavior. During the first year it is impossible to predict how an individual customer may respond to the flat bill. But the overall average response can be anticipated and distributed evenly into all customers’ flat bills during the first year. In fact, changes experienced with customers volunteering for budget billing can be used as a good first approximation. When a customer renews their offer, however, their actual usage with their demonstrated behavior change could be built into the renewal offer instead of that for the average customer. This practice in itself can be expected to reduce inefficient consumption changes.

An additional risk is that a customer might use more electricity during the first year than predicted, and then decide not to renew. This “free-ridership risk” can be measured and forecasted. The predicted impact can then be built evenly into all future customers’ flat bill offering. We theorize that even if participants return to the traditional pricing tariff, they will retain some residual behavioral changes that will generate further profitable sales.

Finally, you have risk associated with the accuracy of the cost variable going into the flat bill pricing model. That variable includes the predicted base energy price and fuel price, customer billing history, predicted customer behavior and the accuracy of the weather-normalization model. How does the flat bill compensate the supplier for these financial risks? The answer is the risk adder. We have already determined that customers are willing to pay a premium to have this risk transferred to the supplier, so if customer sensitivity to the risk adder is equal to or greater than the acceptable risk of these components, then this portion of the risk can be managed.

To manage the portfolio of financial risks, we created a spectrum of potential outcomes based on all risk variables. We tested the severity of these risks by creating a range of worst-case, expected and best-case scenarios, where the risks can be quantified and therefore managed through the flat bill price.

Reality Check. The financial results of the pilot during the 12-month period supported the hypothesis that the risk could be managed. The actual outcome fell within the risk spectrum and very close to where we predicted given the actual outcome of each risk variable. That does not mean that the financial results were positive. In fact, during the 12-month period we experienced a hot summer, a mild winter and an increase in fuel price. Though that caused Georgia Power to see a negative financial impact for the flat bill customers, it supported the natural hedge theory because the company earned a higher than normal return from weather-sensitive customers not taking the flat bill.

The program is not designed to win every year; rather, it’s designed to earn a given return over multiple years. The scenario is similar to the bet a casino wagers. On any given roll, a customer can beat the house, but over a course of multiple rolls, the odds are set so that the house comes out ahead. Referring back to the free-ridership risk, most casinos “bet” that few winners will walk away from the table immediately after winning. The analogy with the flat bill is that even those few who leave the program will maintain higher consumption habits, which have become embedded in their behavior and will be captured in normal tariffs. The trick is managing the risk.

Norm 4: Regulators Won’t Approve It. Even if the potential load growth is manageable, customers want it and the risks can be managed, many suppliers believe that commissioners in regulated regions will be opposed to the program’s innovation and risk.

It’s easy to understand why regulators would scrutinize this product. The industry norms suggest that there are established opinions against such a product. But we believed that by challenging each of these norms through market research, modeling and risk analysis, this product could be approved and introduced into the regulated electric market. After all, IPALCO had received regulatory approval in 1998 and offered a similar product ever since. In addition, we could address regulatory concerns through standard regulatory accounting to shelter regulated non-participants of the program from flat bill risk, exposing only utility stockholders.

Reality Check. In June 2000, Georgia Power received regulatory approval for a one-year pilot with a maximum number of 500 participants. The utility recently earned approval to expand the offering to 100,000 customers with no cap on participation.

Managing Flat Bill Risk

Energy companies can manage the financial return of a flat bill program based on its appetite for risk. It’s kind of like having your foot on your car’s accelerator: You can press down to go faster or release it to slow down. Likewise, there are two simple methods to control your risk and return.

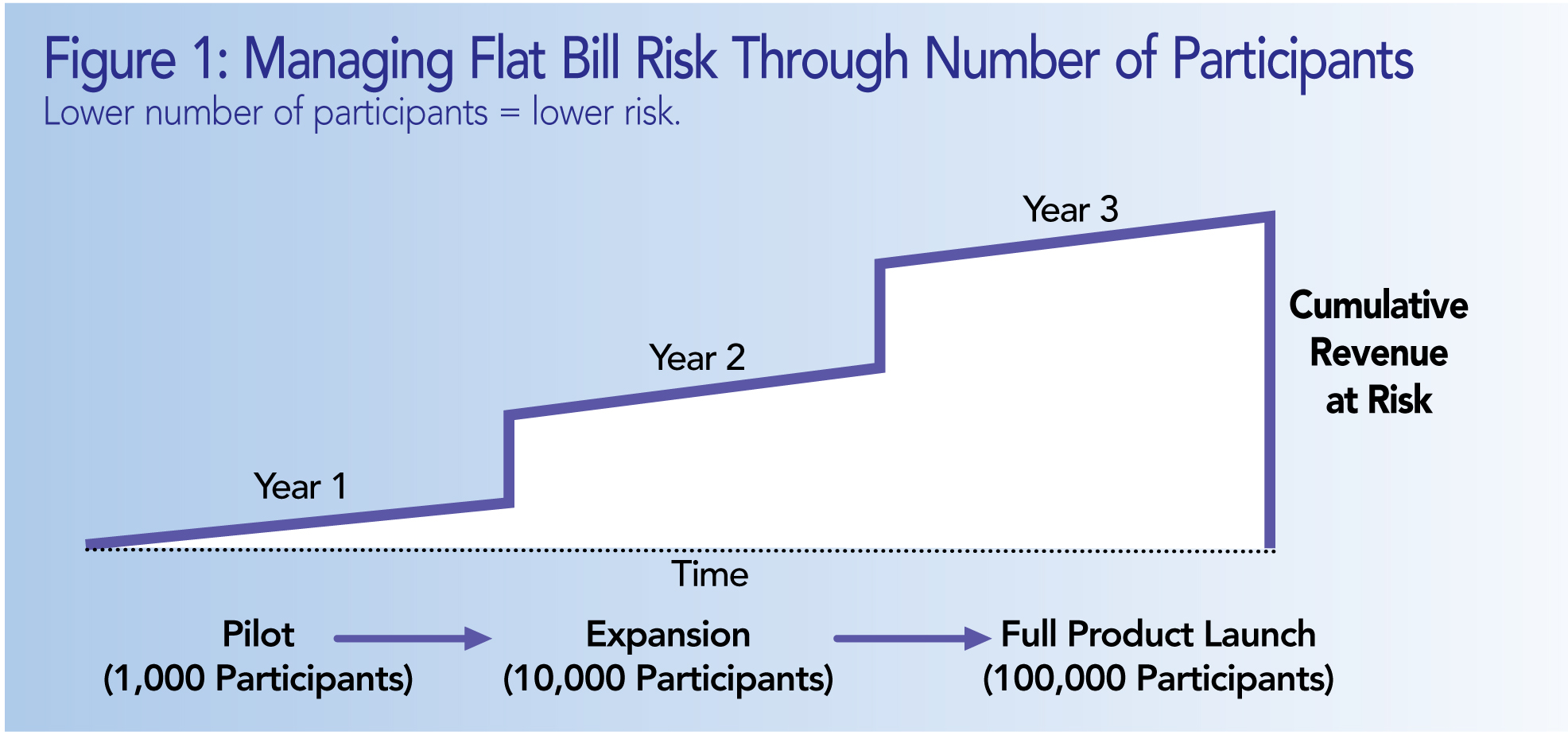

The first method is managing the number of participants (see Figure 1). You can phase the program in by offering a small pilot, then slowly expand eligibility to larger markets. That can give you time to assess risks and returns and make small adjustments to the pricing model, as well as to the program’s terms and conditions.

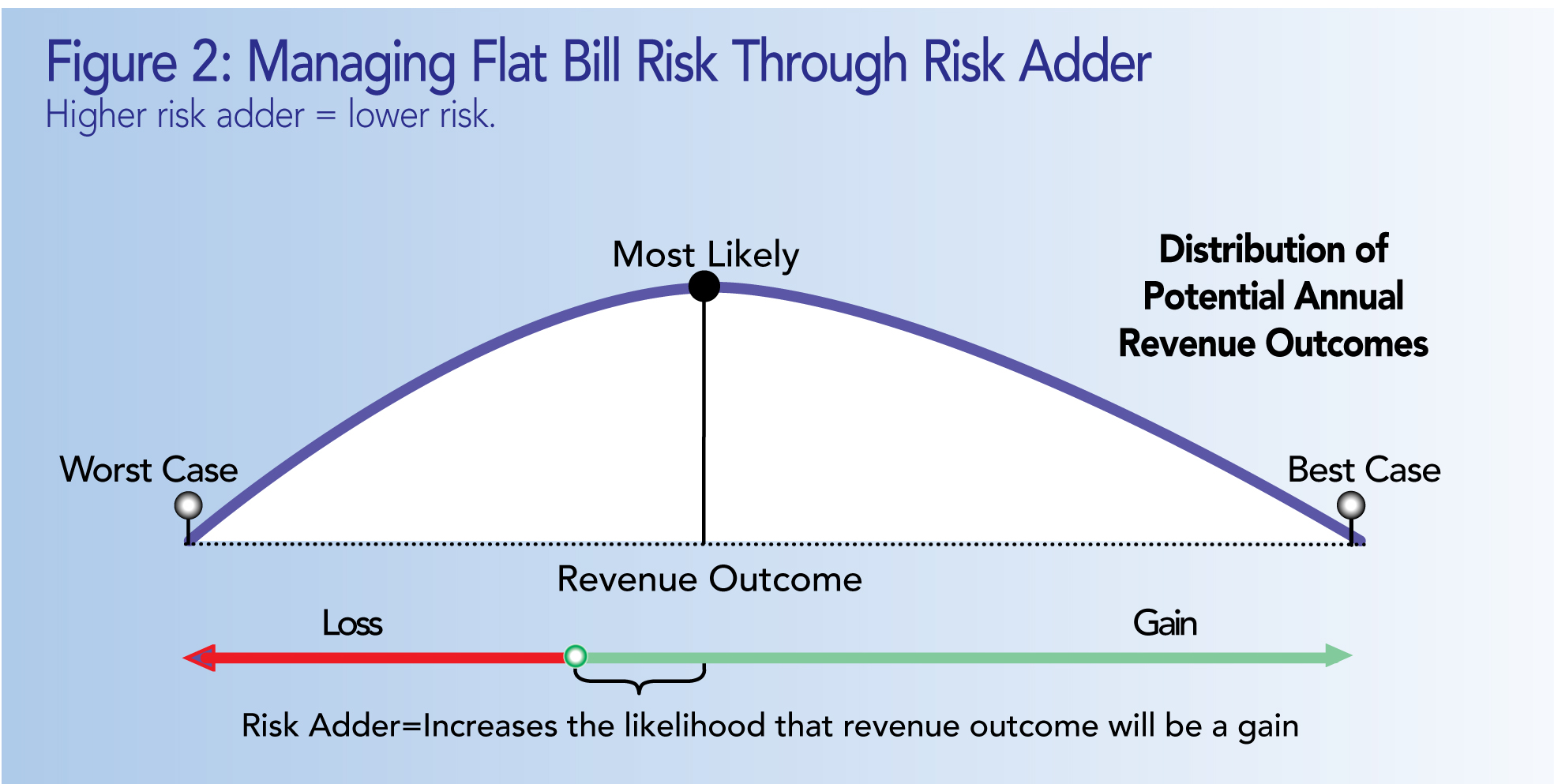

The second method is to manage risk through a risk adder (see Figure 2). The risk adder is the premium charged to compensate the company for the additional risk it assumes. In any given year, the program could take in more or less money than what customers would have paid under the tariff-based, volumetric-pricing plan. Increasing the amount of the risk adder increases the likelihood that in any given year, the revenue outcome for the company will be a gain. Of course, the larger the risk adder, the smaller the participation rate.

In an industry built on the bricks and mortar of unit price efficiency, some will continue to scoff at this pricing innovation, dismissing flat bills because of the perceived inefficiency. We suggest those skeptics carefully examine the many industries offering flat bills. Consider the Internet service providers offering unlimited use for $19.95 per month; the telecommunications firms hawking unlimited use at $60 a month; and auto rental companies with unlimited miles for $40 per day.

There is a market niche yearning for such a product, and it can be constructed safely and profitably. It simply requires that you clearly define the norm and logically address it. If you don’t, someone else will.

Category (Actual):