New approaches account for the economic benefits of renewables.

Lori A. Bird and Karlynn S. Cory are both senior energy analysts with the National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL). Blair G. Swezey is senior director of solar markets and public policy at Applied Materials, and formerly was a principle policy analyst at NREL.

Clik here to view.

Clik here to view.

Clik here to view.

Clik here to view.

Clik here to view.

Clik here to view.

Clik here to view.

The guiding principle of voluntary green power markets is that electricity consumers can choose to purchase electricity derived from renewable energy, as distinguished from the standard power system mix.1 The willingness of consumers to make these purchases, almost always at higher cost, rests on the value they receive in return, which usually comes in the form of environmental benefits. However, environmental improvement benefits the broader public, not just program participants; everyone benefits from a cleaner environment regardless of who pays for it. The overall success of the voluntary green power market rests on the willingness of large numbers of individual consumers to pay more for these electricity products, despite the fact that environmental benefits accrue to the public at large.

At the end of 2007, more than 600,000 residential and business customers were participating in utility green power programs, which are offered by about 25 percent of utilities nationwide. Customer participation rates in these programs averaged about 2 percent, with the top programs averaging from 5 percent to 20 percent.2, 3 Detailed analyses of utility programs have found that the top performers often offer a superior value proposition to consumers (e.g., Wiser et al., 2004). Others advise that the value proposition is of critical importance for garnering the participation of corporate customers.4 There are a number of “private” benefits that utilities often provide to their green power customers, such as individual and public recognition, offering discounts and promotions at local businesses, and providing decals for display in windows of businesses that purchase green power.5

An increasingly important value is a fixed-price, rate stability benefit reflecting the fixed costs of the renewable energy sources used to supply the program. The small number of green pricing programs that offer this benefit protect or exempt their participants from the portion of rate increases that stem from fuel costs. In so doing, these stable-price programs provide a hedge, a kind of insurance policy, against fossil fuel price increases. In a period of dramatic price increases and price volatility, particularly in the cost of natural gas, the draw of such a benefit is apparent. This article examines utility experiences when offering the fixed-price benefits of renewable energy in green pricing programs, including the methods utilized and the impact on program participation. It focuses primarily on utility green pricing programs in states that have not undergone electric industry restructuring.6

Plant Cost Structures

A relatively high fraction of the overall cost of a renewable generation project is expended on equipment for resource collection and conversion. With the exception of biomass resources, the renewable fuel used in the plant operation is essentially free.7 Because these investment costs are incurred up front, the cost of generation from most renewables-based plants is stable over time, subject only to variations in operations and maintenance (O&M) costs and resource availability, which tend to be predictable.8 Thus, whether a utility owns its renewable generation or purchases renewable energy through a power-purchase agreement, the price is known and essentially fixed over time.9

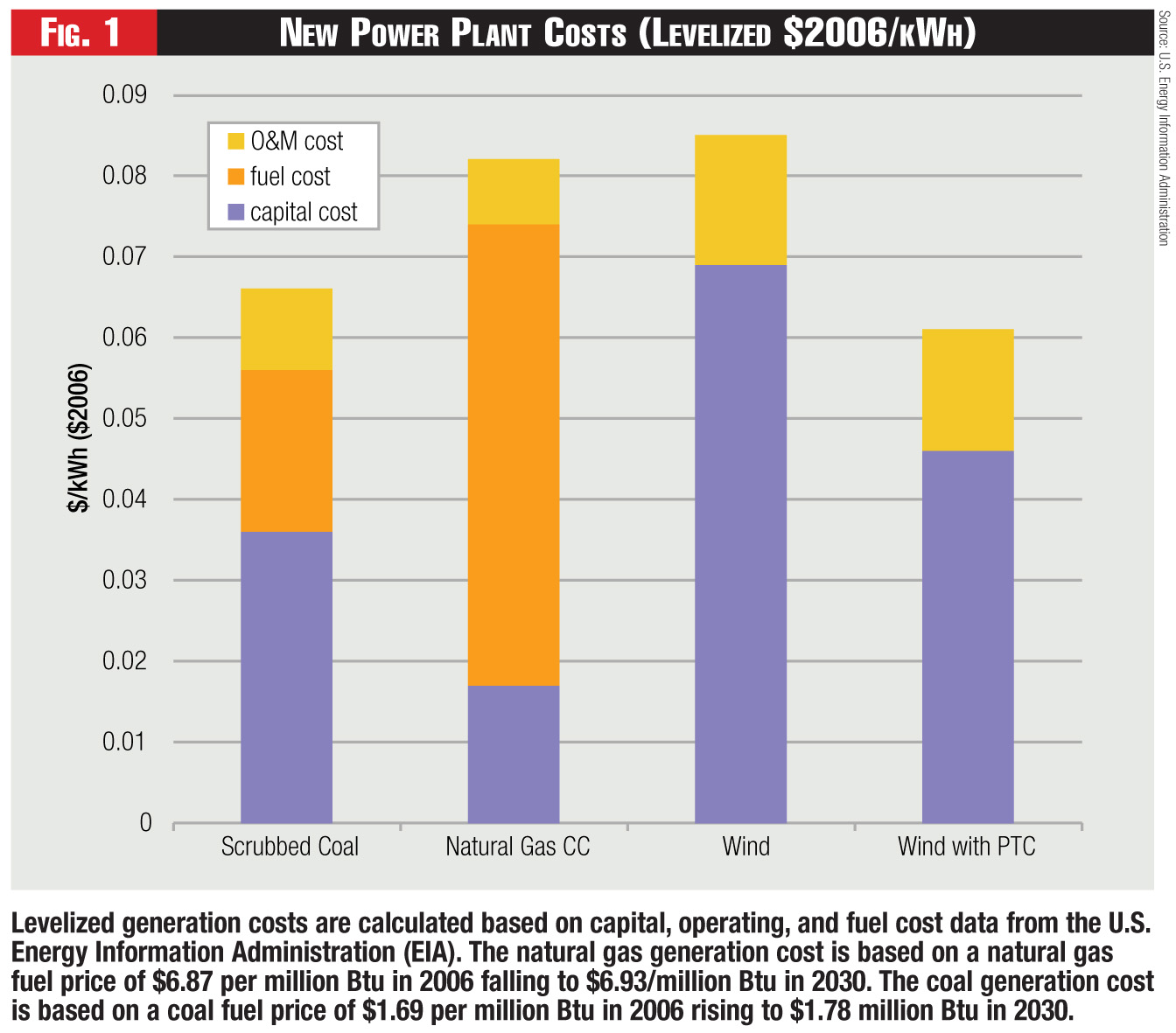

There are large differences in the structure of the costs among generating sources. For example, the majority of the projected generation cost for the wind plant is in the up front capital investment, while most of the natural gas generation cost is in the fuel expense (see Figure 1). The challenge for capital-intensive power projects is that the up front cost of power projects usually receives greater scrutiny from utility regulators. However, the long-term costs and rate impacts of projects with significant fuel costs are dependent on fuel price projections that cannot be known with certainty. Furthermore, once the project is in operation, fuel price increases and decreases tend to be passed to customers through periodic, real-time fuel price adjustments. The initial capital costs of power plants are more predictable than fuel costs and easily can be planned into electricity rates.

Although nearly 50 percent of U.S. electricity supply is generated from coal, the natural gas generation share has been increasing—natural gas generation now accounts for 20 percent of U.S. electricity generation compared to 13 percent just 10 years ago. Notwithstanding commodity price trends in late 2008, the growing dependence on natural gas as a generation fuel has caused electricity prices to increase significantly.10

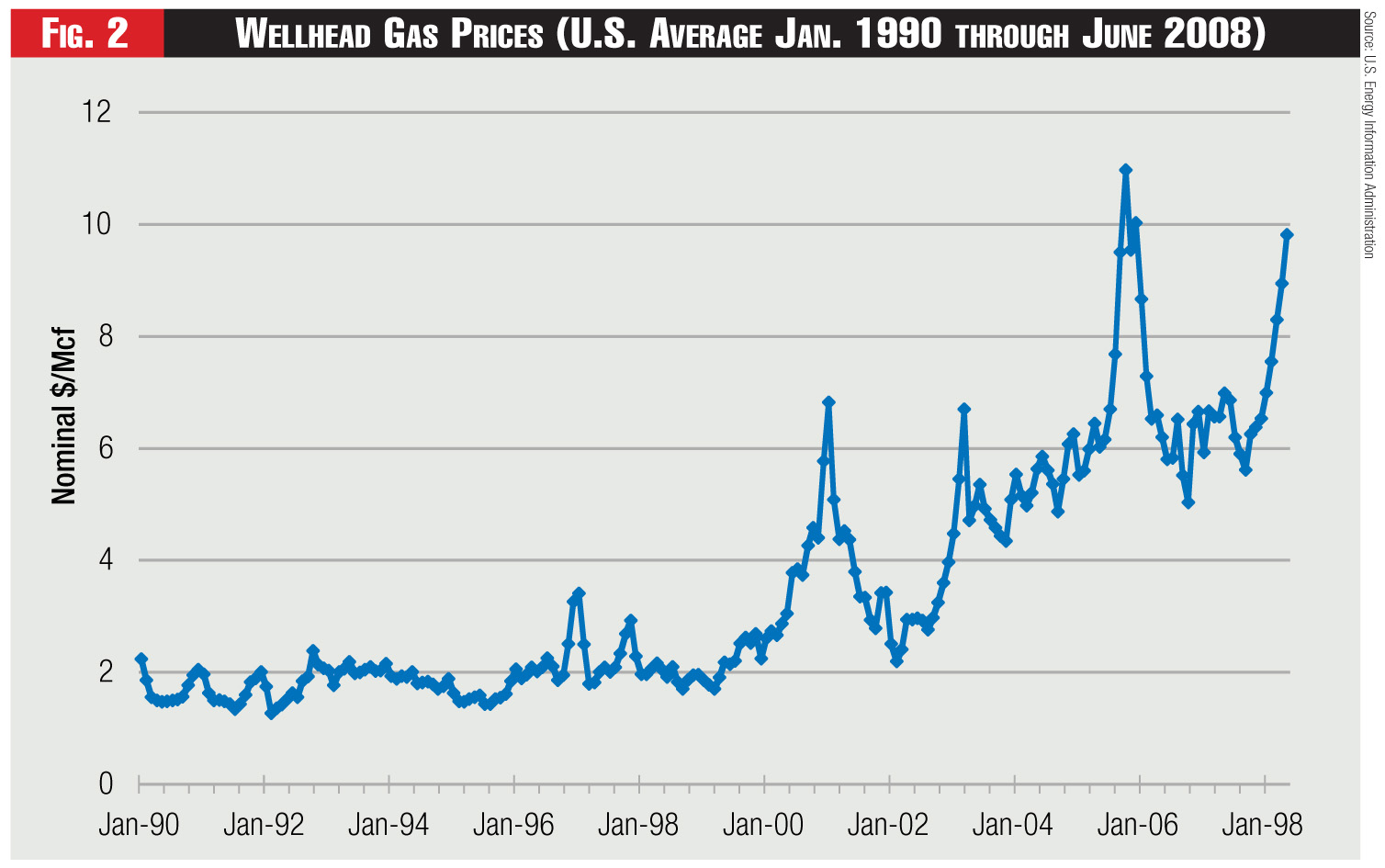

Recent trends in natural gas prices have highlighted the risks inherent in reliance on fuel-based technologies without fixed-price fuel contracts (see Figure 2). Not only have higher prices been a burden, but the volatility of prices also is problematic for both operations and planning.

Even coal-fired generation is subject to fuel-price escalation and volatility. U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA) data show that the average cost of coal delivered to U.S. electric generating plants rose 30 percent from 2004 to 2007 as a result of both minemouth price increases as well as transportation cost increases.11 And spot market coal prices have increased even more dramatically, with Central Appalachian coal prices exceeding $140 per short ton in the summer of 2008 compared to about $45 a year before.12 Coal generation costs also might be subject to future emissions control costs (i.e., for carbon and mercury), which generally aren’t reflected in current or projected plant costs.

Typically, these cost increases are passed on to ratepayers. As a result, some electricity customers are beginning to value renewable energy generation for its stable-price characteristics in addition to the environmental benefits. And green power customers are beginning to expect to receive this fixed-price benefit as a component of their product purchase.13

Valuing Fixed-Price Renewables

What motivates consumers to purchase green power? Utility market research has found that for residential customers, the decision is predominantly an emotional one; while for commercial customers, it is a business decision.14 Both sets of consumers often are interested in purchasing green power for its environmental and fuel diversity benefits, and out of an interest in preserving resources and the environment for future generations.

For commercial customers, green power purchases can be motivated by an interest in “doing the right thing,” generating customer, shareholder, or employee goodwill, meeting corporate or organizational goals for sustainable business practices or operations, or for financial reasons, such as mitigating potential penalties for greenhouse gas emissions in the future or providing a hedge against fuel price volatility.15,16 Green power purchases also can be a market differentiator for businesses, and provide co-marketing and co-branding opportunities. And many large purchasers report receiving valuable earned media and other public recognition as a result of their purchases.

The fact that green power commands a premium is a key factor keeping market penetration low. Recent experience shows that when green power prices reach or fall below parity with base rates, a greater number of customers will make purchases. Research conducted by Portland General Electric shows that even though the key drivers for customers to sign up for the utility’s green pricing program are environmental, customers in the segment who were undecided about signing up for the program would be persuaded to enroll if they personally benefited from lower rates in the long run.17 Therefore, even customers who primarily are motivated by environmental reasons might be more inclined to participate if the program offered price stability or a hedge against fossil fuel cost increases.

With rising fossil fuel and electricity prices, businesses increasingly are looking for price stability in their green power products in order to hedge themselves against rising prices.18 Even if renewables might be more expensive initially, the availability of a fixed-rate product over a long time period provides much-desired certainty in energy expenditures. This certainty can help businesses better plan their budgets.

Austin Energy has found that its business customers most value the price certainty and savings that come with the utility’s fixed-rate product. Advanced Micro Devices (AMD), an Austin Energy green-pricing program participant since the program began, noted that the fixed-rate product allows the company to reduce overall energy costs.19

While there is a lot of interest in capturing the value of fixed-price renewable power, it might not be straightforward to execute in a green power program. Utilities face an array of challenges when initially determining a price of a green power product and considering how it should change over time.

Pricing Green Power

In the rate-setting process, utilities can choose among several green pricing methodologies that account for the cost differential between renewable energy and conventional energy sources.

In the simplest sense, electricity rates reflect cost recovery of a utility’s investments and operating expenses. These costs include: 1) owning generation; 2) owning transmission and distribution assets; 3) a return on owned assets; 4) purchased-power contracts; and 5) recovery of various operating expenses, including fuel costs, maintenance and administration. Generation, transmission and distribution costs traditionally are rolled up or bundled together into a utility’s rate20 and not tracked separately in traditionally regulated electricity markets.21

Because utility costs are bundled together, all generation resources are combined to create a utility system mix of generation. In other words, utilities normally don’t distinguish between individual generation sources for their customers. Therefore, an equivalent mix of the utility’s generation resources and purchased power is provided to each customer.

For green power programs, utilities and regulators are interested in separating the specific costs related to securing green power. In this way, green power products are unique, differentiated electricity products. Since customer participation is voluntary, only those customers that choose to sign up for these programs pay the incremental costs. Green power program participants typically pay the higher cost of renewables in the form of a premium on their monthly bill. There are four main components to the determination of the green power premium:22

1. The cost of the green power source: This includes the total cost of electricity and environmental attributes from all renewable resources used in the product, whether from wind, solar, geothermal, biomass, or another source, and whether owned by the utility or acquired through a power-purchase contract. The cost of the green power sources are captured through the specific power-purchase agreements for renewable energy or renewable energy credits (RECs), or through the regulatory approval process for utility-owned renewable projects. As long as these are tracked separately from the rest of the generation mix, the appropriate renewable generation costs can be determined. One challenge in determining generation costs results from the uncertainties regarding how many customers will enroll in the program and for how long they will participate.

2. Program implementation costs: Any additional costs attributed to implementing the green power program, including administration and marketing. It is relatively straightforward to determine a program budget. First, the cost of program administration directly is linked to the staff, equipment, and other resources used to administer the program. Second, the marketing costs can be estimated based on the marketing methods used to publicize the program (e.g., bill inserts, participation in community events). The challenge for determining the level of marketing expenditures lies in determining the appropriate amount of resources needed to attract a sufficient number of customers to the program.

3. Ancillary services costs: The additional costs incurred to integrate variable output resources, particularly wind, into a utility’s system. Ancillary services guarantee the reliability and security of the electric system by responding to constantly changing electric grid conditions. They are the set of activities and functions that electric system operators and market participants perform in order to: 1) balance electricity supply and demand on a minute-by-minute basis; and 2) prepare for longer-term changes in supply and demand over time.23 Some renewable energy generators, such as those based on wind and solar, have variable output—they cannot be turned on or off to meet changing demand. Moreover, their output can fluctuate over a matter of a few minutes or hours. Managing these fluctuations can add costs to the system. These costs largely depend on the level of penetration of the variable-output renewables.

4. The cost of displaced utility generation (and capacity) resources: The renewable resource displaces electricity that the utility otherwise would have generated or purchased. The treatment of the cost of the displaced generation resources is the final consideration in determining the green pricing premium. However, defining exactly which generation resources are displaced frequently isn’t a straightforward exercise. While utilities typically don’t publicize the methodology for determining the price of their green power products, enough information is available to cite a number of methods. Some utilities have determined the green power rate using the embedded energy costs from all other generation sources, while others used avoided cost calculations. Generally, the term “energy costs” refers to the operating costs of the generation facilities, including fuel costs and any power purchases, and might or might not include the levelized capital costs that repay the utility for past construction of its existing generation facilities.

Therefore, the green power premium can be represented as: Green power premium = (1) + (2) + (3) – (4)

Adjusting the Green Premium

There are a number of circumstances that might lead a utility to adjust its green power premium. Several terms in the equation used to determine the premium may change over time, including the cost of the renewable energy sources, program implementation, ancillary services, or the cost of the utility’s nonrenewable generation sources. The methods of adjusting the premium can be characterized as either “static” or “dynamic.” A static adjustment reflects a one-time premium change, while a dynamic adjustment denotes use of a regular premium adjustment mechanism. A utility could employ both static and dynamic mechanisms (i.e., exempting green power customers from fuel cost adjustments and making periodic adjustments to the premium).

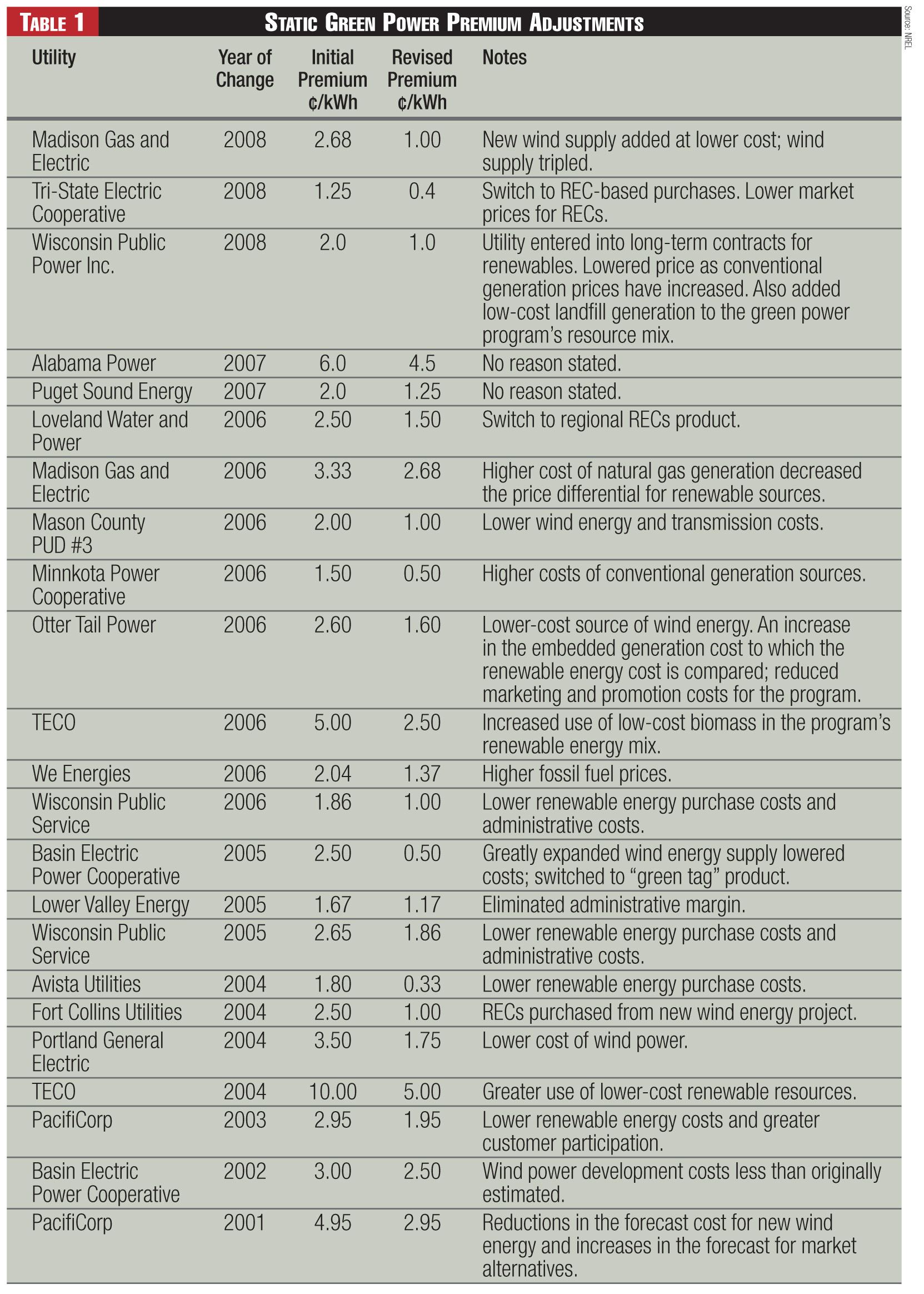

• Static Premium Adjustment: Although it is not common practice, a number of utilities have adjusted their green power premiums over time, almost always resulting in a premium reduction (see Table 1). The reasons behind the adjustment fall into the following general categories:

1) Changes in the cost of the green power source: Renewable energy costs were lower than originally envisioned; the program was expanded, incorporating lower-cost renewable energy sources that lowered the overall blended renewable resource cost; the utility switched to the use of RECs at lower cost; and the actual cost of transmission of renewable energy was lower than projected.

2) Program implementation costs: Lower administrative or marketing costs; and increased customer participation, which enables the utility to spread the fixed costs of program administration over a larger base lowering the ¢/kWh cost burden.

3) The cost of displaced utility generation (and capacity) resources: Increase in the cost of conventional generation sources.

• Dynamic Premium Adjustment: Although static premium adjustments help narrow the renewable energy price differential and encourage greater program participation among utility customers, they don’t capture the dynamic nature of energy price differentials. Both fuel and electricity prices fluctuate annually, seasonally, daily, and even hourly as they are impacted by electricity demand, changes in the market perception of domestic and global fossil fuel supply and demand, construction of new power plants, electricity transmission congestion, and other factors. Utilities dynamically can adjust the green power premium in two different ways, by: 1) exempting customers from fuel-cost adjustments, and 2) substituting a fixed green rate for the energy rate on the customer’s bill.

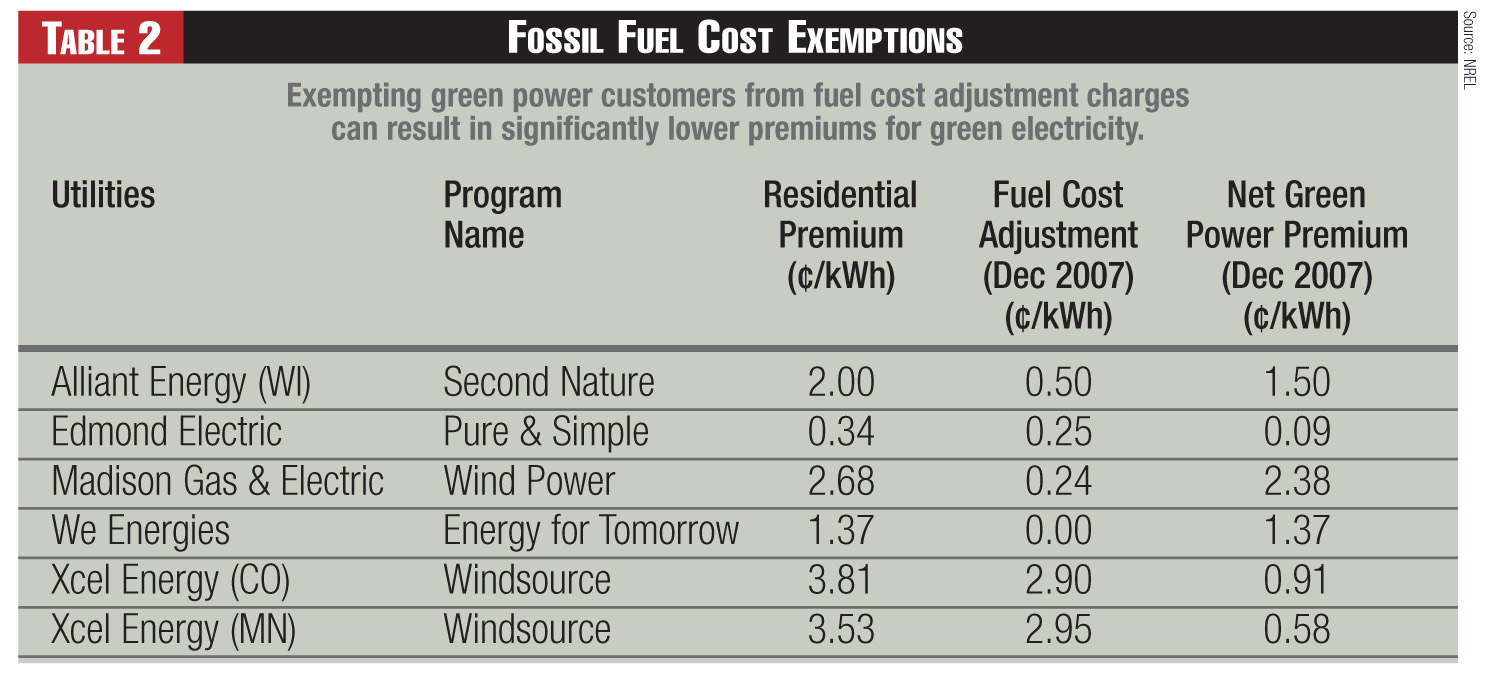

As fuel costs have risen, the use of a fuel cost adjustment (FCA) has become prominent in the utility industry. The Edison Electric Institute (EEI) defines an FCA as “a clause in a rate schedule that provides for an adjustment to the customer's bill if the cost of fuel at the supplier's generating stations varies from a specified unit cost.”24 Use of an FCA allows a utility to automatically pass through higher (lower) fuel costs—as an adder (credit) to the base rate—rather than wait for formal rate change approval.25 A handful of utilities exempt their green power customers from the FCA under the rationale that green power customers should be protected from costs associated with the utility’s fossil fuel or other non-renewable generation sources and for their commitment to support renewable energy sources.26

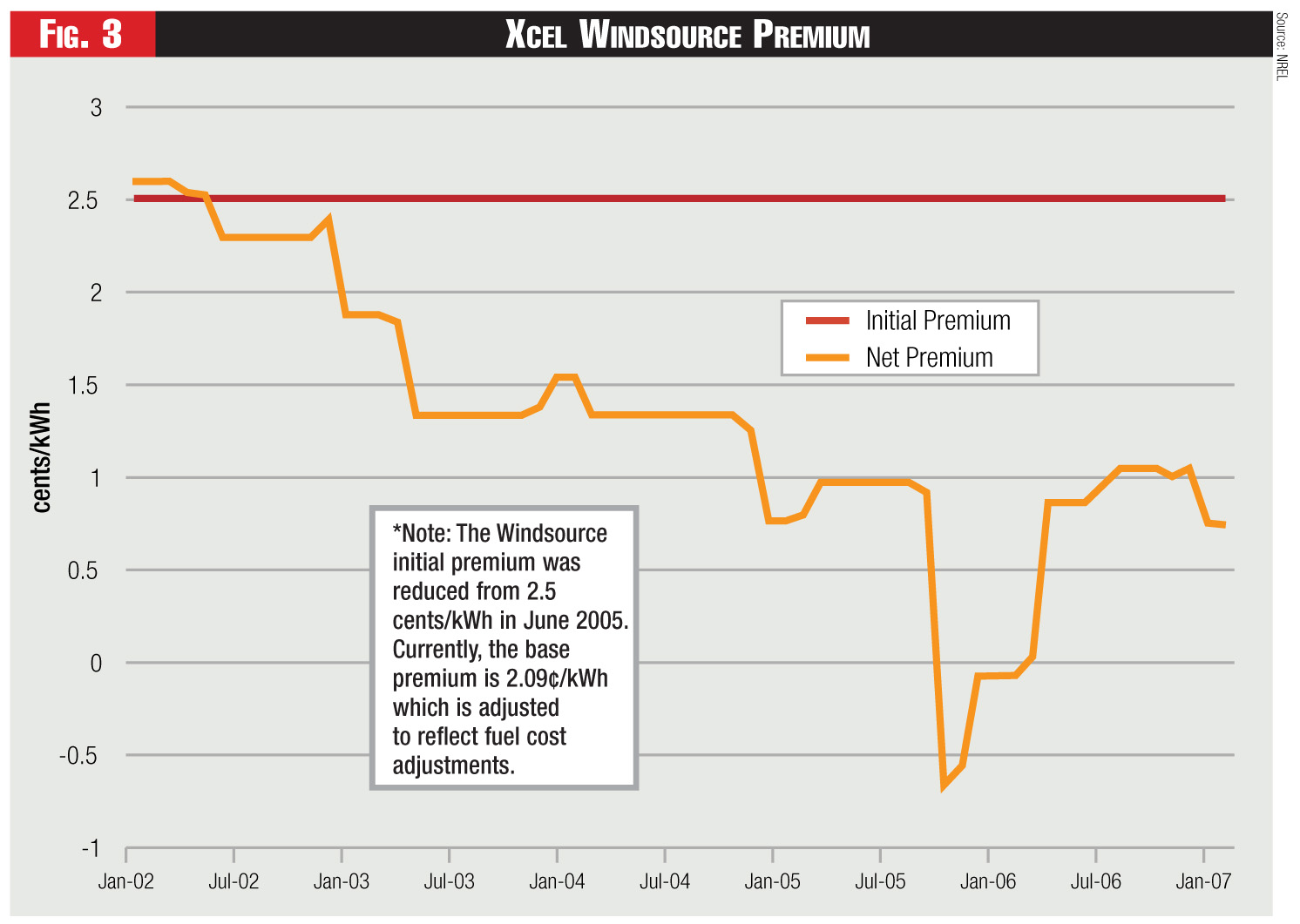

FCA exemption can have a marked impact on the effective or net price differential (net green power premium) (see Table 2). For example, the net green power premium for Xcel Energy in Colorado over time, compared to the (theoretical) case where the initial green power premium could have remained constant (see Figure 3). As shown, the net premium significantly was reduced (and even went negative for a time), as a result of the FCA exemption.

Unfortunately for many green power customers, the FCA represents a short-term collection mechanism used between major rate cases that eventually gets balanced in the next utility rate case. Therefore, in many cases, these higher fuel costs eventually become part of base rates and the FCA is set back to zero, eliminating any pricing benefit. For example, in Wisconsin, Second Nature customers served by Alliant-Wisconsin Power & Light (WP&L) were exempted from FCA surcharges instituted after Jan. 1, 200127 (see Table 2). Two fuel cost increases totaling 0.58¢/kWh lowered the net green power premium to 1.42¢/kWh by the middle of 2001, but a fuel-cost decrease of 0.19¢/kWh increased the premium to 1.61¢/kWh in March 2002. In the summer of 2002, the Public Service Commission of Wisconsin (PSCW) approved a rate increase that incorporated the utility’s additional fuel costs into the base rate energy charge, eliminating the fuel-cost surcharge and reestablishing the Second Nature premium at the full 2¢/kWh.

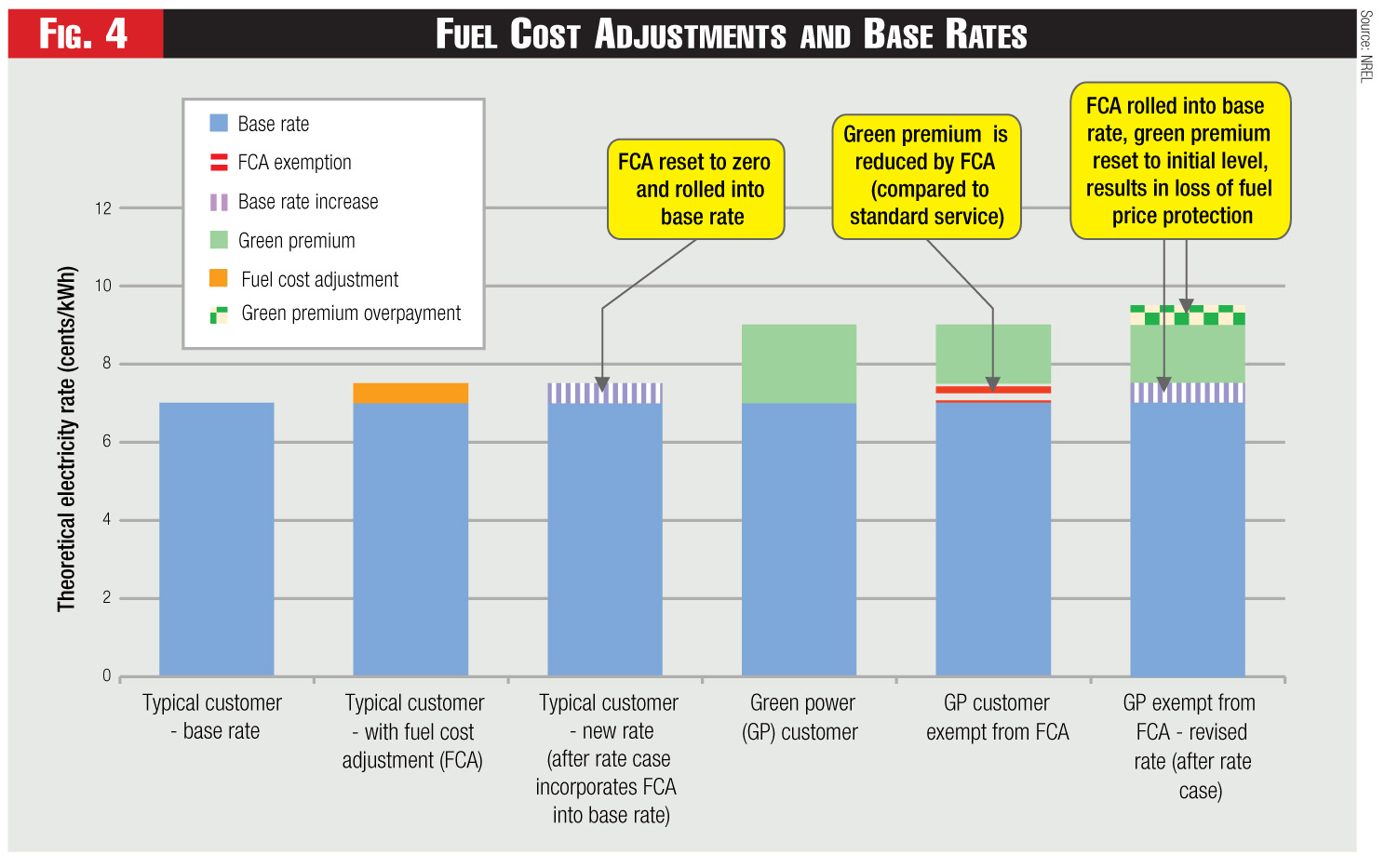

A typical customer’s base rate is adjusted up (or down) depending on the actual cost of fuel for electricity generation (see Figure 4). Once the base rate is adjusted, the green power customer pays the new base rate, plus the green power premium, which is higher (or lower) than they should be paying, based on the fixed-price cost of the renewable resources. Therefore, if the green- power premium is not adjusted to account for upward changes in the cost of conventional generation, green-power customers continue to pay a higher premium rate even as the cost differential between renewables and non-renewables narrows.

Also, focusing only on FCA exemption might ignore energy costs already embedded in rates. The amount of fuel cost embedded in base rates can be significant, particularly in recent years. For example, OG&E increased the amount of fuel costs in its base rates to 2.9¢/kWh from 1.5¢/kWh as part of the 2005 general rate case.

From the consumer’s perspective, the green power premium would be more fairly priced if it were revisited every time there is a rate case to account for the difference between the cost of the renewable energy resources and the utility’s non-renewable generation mix.28 With rising energy costs, utilities are rolling higher energy costs into base rates, making this issue more significant for green power consumers. Green power customers obtain the fuel-price stability or hedge benefits of their green power purchases only if changes in energy costs are tracked over time and netted from the green power tariff.

Fixed Green Rate

A different approach to protecting green power customers from energy cost changes is to substitute a specific green generation rate for the conventional energy generation rate.29 Under this approach, green power customers pay all of the same charges as base rate customers, including transmission, distribution, billing, and administrative expenses. However, instead of paying the standard generation costs, they pay the cost of the renewable energy generation and any supplemental costs (ancillary services and program implementation costs).

Austin Energy has used this approach in pricing its GreenChoice product, which is supplied primarily with wind energy. A key characteristic of the GreenChoice product is the establishment of a separate green charge, which substitutes directly for the utility’s fuel charge. The fuel charge is a line item on the customer’s bill, consisting of forecasted annual fuel and purchased power costs, and estimated fees and charges from the Electric Reliability Council of Texas (ERCOT) incurred to meet service-area obligations.30 The green charge, on the other hand, is determined by the cost of the renewable energy power-purchase contracts Austin Energy signs to supply the program, plus additional costs such as ancillary services and product marketing, and currently is fixed for 15 years.

The key factor that allows Austin Energy to offer a fixed-rate green power product is that the renewable energy supply is locked in at a fixed rate for 10 to 20 years, depending on the associated supply contracts. Accordingly, business customers, who are the primary target of the program, must commit to the GreenChoice program for a 15-year period,31 reducing the risk for the utility that demand for the renewable energy project will fluctuate. The utility also has an unbundled rate structure, allowing the green charge directly to substitute for the fuel charge on customer bills.

Although offering protection from fuel-price volatility does not guarantee success in and of itself, it has been a key design element of a number of successful utility green pricing programs. For example, Austin Energy’s green pricing program has led the nation in terms of green power sales since 2001 and its program represents about 15 percent of all green pricing sales nationally.32 In addition, a number of utilities that offer some form of fuel price protection to their green power customers have been ranked in recent years among the top 10 U.S. green pricing programs with respect to green power sales or participation, including Xcel Energy, Edmond Electric, Holy Cross, Oklahoma Gas & Electric, and We Energies.33 Programs that offer protection from price volatility also tend to have lower price premiums—about half of the utilities offering the lowest premiums for new renewables exempted customers from fossil-fuel charges or offered a fixed green rate, according to the most recent rankings based on year-end 2007 data.34

But while fixed-rate green power products offer a compelling value proposition to consumers and contribution to program success, most utilities don’t offer such programs for several reasons.

First, the ability to substitute a green rate for either the energy rate or fuel charges (as in Austin) requires an unbundled rate structure. Most utilities in traditionally regulated electricity markets do not explicitly delineate the various utility cost components on the customer bill. Generation, transmission, distribution, and administration costs generally are rolled into a standard service charge and a usage charge.

Second, is the question of risk allocation. Regulated utilities usually enter into long-term power purchase contracts (10-25 years) or decide to own new renewable generation for the life of the project. As state-regulated entities, investor-owned utilities face greater challenges and scrutiny in accepting the risks of long-term renewable energy contracts. If consumers don’t make a similar long-term purchase agreement, the utility is exposed to the risk of absorbing the higher cost of the renewable energy generation, either in base rates or with shareholders. While it might be possible to hold nonresidential customers to long-term contracts if they perceive a hedge value, it is more challenging to hold residential consumers to similar requirements because of their shorter planning horizon.

Third, the adaptability of a utility’s billing system can place some limitations on product design and pricing. According to Mat Northway of Eugene Water and Electric Board, “The billing system often dictates the product, i.e., how easy (or difficult) it is to change the billing system.”35

The challenges associated with billing-system software and programming was echoed by Douglas Smith of Green Mountain Power. Substitution of a green rate for the standard energy rate might be difficult to implement in some billing systems.36

Finally, some utilities might have concerns about what happens if the green power product price falls below base rates. The question revolves around whether or not it is problematic for the utility to provide one resource at lower cost to only one segment of the utility’s customer base. In fact, one utility (Utili-Corp United) decided to abandon its program altogether and roll the renewable energy supplies into base rates when the cost of renewable energy approached that of its conventional energy sources.37, 38 On the other hand, if the product initially is offered at above-market rates and customers are willing to make a long-term purchase commitment, then the customers are accepting the risk and locking into a rate that might (or might not) prove to be beneficial over the long term.

Clearly, Austin Energy has been able to address successfully these issues in offering its GreenChoice program. To address the issue of revenue risk, the utility successfully has required its commercial consumers to commit to 10- to 15-year purchase commitments, which equals the term of its power-purchase contracts. The value of the product as a hedge against future fuel price increases has been a compelling motivator for Austin’s consumers, particularly its nonresidential consumers, to make long-term purchase commitments. The competitive pricing of the Austin product also has contributed to its success, as consumers perceive that achieving future cost savings is possible. If the product is priced too high above standard electricity rates initially, consumers might not see it as a compelling hedge against rising fuel prices.

REC Purchases and Price Stability

Utilities increasingly are supplying their green pricing programs with RECs unbundled from its underlying power.39 If RECs are used to supply the program, can the fixed-price benefits of the renewable energy sources be passed on to consumers? That is, if REC costs are additional to fossil fuel-fired generation costs, do the renewables actually convey a fixed price benefit? Or are those benefits retained by the project owner or passed onto the purchaser of the underlying energy from the renewable energy facility?40

It is possible to structure a hedge product with RECs, but it’s a more complex proposition than if the renewable power were sold bundled with the RECs. To date, a few utilities have structured REC-based hedge products with mixed success.

Two REC-based green power products that also provide a hedge benefit (offered by Portland General Electric and Green Mountain Power) provided several lessons. First, developing such a product is complex and properly structuring the rate can be challenging. Second, if the fixed-price of the green power product is set too high, then the customers might question whether they truly get a hedge value, which might limit program participation. Third, if there are portions of the rate that are beyond the utility’s control, they should be excluded from the fixed-rate product, where it is feasible to do so. Fourth, while the REC-based product provides less risk to the utility because it can enter into shorter-term contracts for renewable supplies, the REC product hedge structure is less desirable and will not result in a true hedge, if the REC price does not reflect the actual cost of the generation. It is therefore difficult to provide a true hedge if the cost is disconnected.

Adjusting for Environmental Costs

The treatment of environmental costs increasingly is becoming an issue for green power consumers, as some utilities are recovering the costs of environmental remediation efforts through surcharges or adders on consumer bills. Should green power consumers pay for pollution control costs or other environmental costs associated with conventional fossil fuel plants if they are purchasing renewable energy generation for their electricity needs?

This question was raised when Public Service Company of Colorado (Xcel Energy) implemented a surcharge on customer bills called the “Air Quality Improvement Rider” to recover the costs of voluntarily installing air-pollution mitigation equipment on several coal plants in the Denver-Boulder metropolitan area. The Colorado PUC decision on the matter called for participants of the utility’s Windsource green power program to be exempted from the rider for all of their wind energy purchases.41 On the other hand, the Minnesota PUC approved an “environmental improvement rider” in March 2004 for Northern States Power (NSP) that did not exempt Xcel’s Minnesota Windsource customers. NSP successfully argued that “although participants in the green pricing program help encourage the diversification of our energy supply, they also benefit from the nonrenewable portions of the utility system and appropriately should share in its costs.”42 Recently, there has been increased attention focused on the risks associated with CO2 emissions from power generation and interest in mitigating these risks. In response to growing concerns about global climate change, many states and municipalities, as well as several U.S. regions, are adopting policies aimed toward reducing CO2 emissions. Some of these efforts might affect consumer electricity rates or result in surcharges on consumer bills.

Finally, a number of utilities recover costs for implementing renewable portfolio standard (RPS) policies that require the utility to procure renewable energy to meet a portion of their retail electricity sales. In some cases, these costs are being assessed as a separate adder to utility bills, but for the most part, these costs are rolled into the utility’s base rate. Either way, how should these charges be assessed to those green power consumers who already are paying a premium to obtain 100 percent of their electricity from renewable energy sources? If these consumers are assessed the RPS charge and pay a green power adder for all of their electricity needs, they might be charged twice for a portion of their renewable energy purchases.

Green Value Proposition

The overall success of the voluntary green power market rests on the willingness of large numbers of individual consumers to pay a premium for these electricity products. Accordingly, electric utilities must present a compelling value proposition for their green power products. The stable-price characteristic of renewable energy generation offers an important and appealing benefit for many consumers. However, the availability of stable-price green power products does not guarantee program success. Other factors are important as well, such as program awareness, the extent and effectiveness of program marketing, and the overall pricing of the product compared to conventional electricity rates.

Several approaches exist to provide green power customers with the stable-price benefits of renewables and provide a hedge against increasing fossil fuel prices. The most straightforward method is to establish a separate green power rate that substitutes for a utility’s conventional energy or fuel rate. However, this approach requires both an unbundled rate structure, and for the utility to enter into long-term contracts for the renewable energy resources used. The latter condition presents some risk to the utility and its ratepayers if the program is undersubscribed.

An alternative approach is to exempt green power customers from fossil fuel-cost adjustments. However, because FCAs are an interim measure for addressing fuel-cost changes between rate cases, this approach only provides longer-term fuel-price protection if properly structured. In the short-term, FCA exemption provides a stable-price benefit to green power customers, but the benefit is negated if higher fuel prices become embedded in base rates without a comparable downward adjustment of the green power premium.

Finally, utilities simply can revisit the green power price premium when significant fuel price changes occur or when base rates are adjusted, and consider whether the green-power premium also should be adjusted as a result. This is the most common approach used by utilities over the years. And there is an open question as to whether green power customers also should be exempted from rate changes resulting from utility expenditures to reduce air emissions from fossil fuel combustion or from state renewable portfolio standard requirements.

The key challenges with all three approaches lie in accurately determining the conventional generation costs that are displaced by the increased utilization of the renewable energy resources and designing price structures that are fair to both green power consumers and nonparticipating ratepayers.

Endnotes

1. Standard power system mix typically includes electricity generated from fossil fuel and nuclear sources.

2. Bird, L.; Kaiser, M. (2007). Trends in Utility Green Pricing Programs (2006). NREL/TP-640-42287. Golden, CO: National Renewable Energy Laboratory.

3. NREL (April 22, 2008). “NREL Highlights Leading Utility Green Power Programs.” News release. Accessed April 28, 2008.

4. Hanson, C. (December 2005). “The Business Case for Using Renewable Energy.” World Resources Institute, Corporate Guide to Green Power Markets, Installment 7.

5. Bird, L.; Kaiser, M. (2007). Trends in Utility Green Pricing Programs (2006). NREL/TP-640-42287. Golden, CO: National Renewable Energy Laboratory.

6. In most restructured states it is more challenging to offer stable-priced products because of the long-term contracting challenges and lack of generation ownership. However, it might be possible to develop stable-priced products through the use of renewable energy certificates (RECs), which is discussed briefly.

7. In general, biomass processes are unique among renewables in sharing the combustion process with conventional fossil generation (i.e., biomass facilities procure and burn fuel regularly to produce power over time). For a few biomass generation processes, like anaerobic digestion at a wastewater treatment plant, the fuel might be free.

8. The uncertainty associated with generation from variable renewable energy technologies (such as wind and solar that are available when the wind and solar resources are available) typically is reflected in ancillary service costs, which is addressed at length later in the paper

9. It is important to note that while some contracts with renewable project developers have a simple annual percentage escalator, such escalators are an artifact of typical industry practice rather than an increase in actual costs over time.

10. Energy Information Administration (EIA) (2007). Electric Power Annual with Data for 2006. DOE/EIA-0348. Washington, D.C.: Energy Information Administration, U.S. Department of Energy. October.

11. Energy Information Administration (EIA) (2008). “Cost of Fossil-Fuel Receipts at Electric Generating Plants.” Monthly Energy Review, July.

12. Energy Information Administration (EIA) (2008). Coal News and Market. Accessed June 2008.

13. Green-power customers in Long Island voiced frustration over being charged for rate increases due to non-renewable fuels. For example, see “Lawmaker Says Some Feel ‘Ripped Off’ by LIPA’s Alt-Energy Plan,” Newsday, May 25, 2006. Similar articles appeared in the press in Connecticut.

14. Capage, A. (July 2001). “Across the Green Divide: The Macro Lessons.” Presented at the 6th Annual Green Power Marketing Conference.

15. Hagen, K. (April 2006). “Conversation with REI Corporate Social Responsibility Program Manager.” See also REI (March 28, 2006). “REI Steps Up to 20 Percent Green Power.” News release.

16. Holt, E.; Wiser, R.; Fowlie, M.; Mayer, R.; Innis, S. (2001). “Understanding Nonresidential Demand for Green Power.” Prepared for the National Wind Coordinating Committee.

17. Hinckley, T. (February 2005). “PGE Flat Rate Wind Power Research.” Presented at the EUCI conference: Marketing Green Power: Profit Opportunities in Selling Renewable Energy.

18. Hanson, C. (December 2005). “The Business Case for Using Renewable Energy.” World Resources Institute, Corporate Guide to Green Power Markets, Installment 7.

19. See “AMD Turns Greener,” Austin American-Statesman, October 24, 2005.

20. It is important to note that there is not a single utility rate that is charged to all customers. The rate usually is distinguished by different customer classes (residential, commercial, and industrial) and generally varies so that large volume purchasers receive a discount.

21. While this report is focused on utilities in states that have not undergone electric industry restructuring, note that utilities in restructured states changed the way that they tracked generation costs. As electricity restructuring propagated throughout several U.S. states in the late 1990s and early 2000s, affected utilities often were required to separate out the generation costs in their rates. This disaggregation was done so that if a customer decided to switch to a competitive supplier, the default utility easily could remove generation costs and replace them with the competitive supplier’s costs. As restructuring is active in only 16 states (including the District of Columbia) today, most utilities are not required to separate their generation costs from other costs.

22. If a utility is using renewable energy certificates (RECs), which represent the environmental attributes of the renewable energy source, to supply the green pricing program, the premium simply would be: (1) the cost of the RECs, plus (2) program implementation costs.

23. Ancillary services help control the short- and long-term operation of generation supply, transmission equipment, distribution equipment and overall system control. The activities through which ancillary services can be provided include: before-hand scheduling of generation and transmission, real-time dispatch of available generation and transmission (i.e., adjust the schedule for current conditions), generation reserves to instantaneously maintain the supply-demand balance (load-following spinning reserve responds to small changes and operating reserves respond to infrequent, large failures of generation and transmission), real-power loss replacement (adjusting for system losses) and voltage control (generation, transmission).

24. Edison Electric Institute (April 2005).Glossary of Electric Industry Terms. Washington, D.C.: Edison Electric Institute; p. 3.

25. “Automatic adjustment clauses” can be used for other purposes as well. See, The Brattle Group, “Electric Utility Automatic Adjustment Clauses: Benefits and Design Considerations,” prepared for the Edison Electric Institute, November 2006.

26. These utilities include: Alliant Energy, Edmond Electric, Holy Cross Energy, Madison Gas & Electric, OG&E Energy Services, We Energies, and Xcel Energy.

27. The following discussion refers to the General Service (Gs-1) rate schedule.

28. Of course, the portion of rate increases for distribution, transmission, and administrative costs would need to be allocated appropriately to green pricing program customers.

29. Utilities that have offered fixed green rates include Austin Energy, Clallum County PUD, and Eugene Water and Electric Board (EWEB). EWEB’s Windpower program, which was launched in 1999, was structured so that a “windpower energy charge” was substituted directly for the utility’s energy charge. The program initially was offered at a premium of 2.7¢/kWh over standard rates, but the effective premium fell over time, and was about 0.91¢/kWh for an average customer at the end of 2005. The program became fully subscribed in 2006 and the utility subsequently launched a new program with a different pricing structure. Under the Clallum County PUD program, which was launched in 2003, customers can purchase green power to meet 100 percent of their electricity needs at a fixed rate of 6.9¢/kWh, which initially represented a premium of 0.7¢/kWh compared to the utility’s standard rate.

30. Like many other utilities, Austin Energy also includes some portion of its energy costs in base rates and thus its GreenChoice customers are not fully excluded from paying these costs.

31. Originally, this was a minimum 10-year commitment.

32. Bird, L.; Kaiser, M. (2007). Trends in Utility Green Pricing Programs (2006). NREL/TP-640-42287. Golden, CO: National Renewable Energy Laboratory.

33. NREL (April 22, 2008). “NREL Highlights Leading Utility Green Power Programs.” News release. Accessed April 28, 2008.

34. ibid.

35. Northway, M. (November 2001). “Marketing Green Power - Reaching Your Customer.” Presented at the Eugene Water and Electric Board workshop on Seattle, WA.

36. Smith, D. (June 12, 2008). Personal communication. Green Mountain Power. Colchester, VT.

37. Aquila (March 14, 2001). “UtiliCorp to Purchase Power Generation From Largest Wind Project Constructed in Kansas.” News release. Accessed 2008.

38. UtiliCorp had been selling a premium-priced wind product to its retail customers since 1999. With the announcement of an additional, larger project, the utility notified its "green pricing" customers that it discontinued the premium product charge and incorporated the renewable energy supplies into its base rates (see http://www.eere.energy.gov/greenpower/markets/pricing.shtml?page=2&companyid=260).

39. This primarily is due to increased availability and verification of RECs, as electronic REC tracking systems are now available in regions across the nation and many states now rely on RECs for renewable portfolio standard (RPS) compliance.

40. The project owner might retain the benefits in the case that the fixed-price renewable electricity is sold as power indexed off of fluctuating electricity prices. Conversely, if the purchaser of the underlying renewable energy agrees to a fluctuating price for power indexed off the electricity market, the project owner could benefit if electricity prices rise and they are able to profit from the difference in their fixed costs and the rising sale price of electricity. Or, if electricity prices decrease, then they developer would get paid less for power produced.

41. Public Service Company of Colorado (PSCO). (June 16, 1999). Decision No. R99-678, In the matter of the application of Public Service Company of Colorado for an air quality improvement rider to recover the costs of voluntary emission reductions in three metro area power plants.

42. Xcel Energy (2002). “Xcel Energy’s Petition for Approval of Rate Rider to Recover Costs of Emissions Reduction Proposal,” Docket No. E002/M-02-633.

Category (Actual):

Clik here to view.