Waking Up in the Future

Ahmad Faruqui is a principal with The Brattle Group. He is an energy economist whose career has been devoted to pricing innovations. He has designed and evaluated a variety of pricing experiments in the U.S. and abroad and maintains a global database of more than three hundred tests of time-varying rates. Faruqui has testified on rate-related issues in several jurisdictions and presents frequently on tariff reforms.

Clik here to view.

Clik here to view.

Clik here to view.

Clik here to view.

Clik here to view.

Clik here to view.

"No one can walk backwards into the future."

Rip Van Winkle, Jr. had spent a beautiful April day hiking in the high Sierras. After a light meal, he crept into his sleeping bag under the Milky Way, began to count the stars, and fell into a deep slumber.

He woke up two decades later. He was a professional energy economist who had cut his teeth on time-of-use rates early in his career. After the California energy crisis, he had become interested in championing dynamic pricing rates to connect retail and wholesale markets.

More recently, seeing the rapid penetration of rooftop solar panels, he had become a critic of simple, two-part volumetric rates that were neither cost-reflective nor economically efficient. He had begun talking of rate designs that would recover energy charges through time-varying rates, recover capacity costs with demand charges, and recover metering, billing and customer care costs with fixed charges.

But he kept running into the same objections in rate case after rate case. The same negative arguments about the harmful effects of dynamic pricing and demand charges were being heard over and over again. They were keeping court reporters very busy in just about every hearing room in just about every state of the union.

The plethora of objections included: customers won't understand them; customers won't respond to them; they are unethical; they will harm low-income customers; and they will remove the incentive for energy efficiency. In other words, if you stick to the current rate design, you can save the world.

A witness opposing rate reform said that people won't be able to even understand dynamic pricing rates, let alone respond to them. The other witness, in his testimony, said that people were already in tune with dynamic pricing in other walks of life. They encountered it when buying airline tickets, renting a car, booking a hotel room, watching a movie or catching a sporting event.

They even saw it in some cities while driving on HOV lanes during commute hours. And they even encountered it at the plain old parking meter. You paid to park between 8 a.m. and 6 p.m. in downtown areas on weekends. The other hours were free.

Another said that one needed to know the differential calculus to understand the concept of demand, since kilowatt demand was obtained by differentiating kilowatt-hour energy with respect to time. The other witness responded by saying that two can play this game. You would need to know integral calculus to understand kilowatt-hour since kilowatts would have to be integrated over time to get kilowatt-hour.

A third said that low-income customers would be harmed. When told that the rates were not mandatory and they could pick whichever rate design worked for them, the answer was that low-income customers would not be able to know that such rates could raise their bills and would sign on to them, lured by the prospect of paying lower prices in the off-peak periods.

They were also informed that many low income customers don't have large appliances and have more than average low load factors and thus would be better off under a time of use or dynamic pricing rate, but it seemed to have no impact on the witness who was opposing rate reform. Of course, these objections had not prevented path breakers from deploying new rate design options even in 2020.

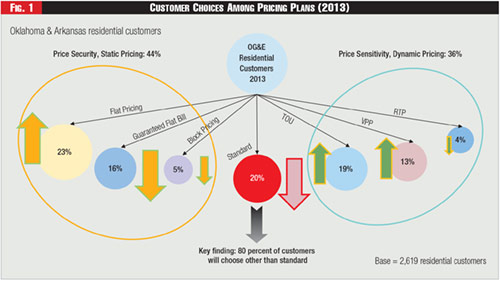

The offerings of some utilities back then had provided a glimpse into the future. Oklahoma Gas & Electric was offering customers a choice of a flat bill, a two-part volumetric flat rate, a time-of-use rate, and a variable-peak pricing rate, with the latter two being offered with Wi-Fi enabled thermostats. These rate choices had been informed by a formal market research program involving customer surveys and conjoint analysis.

See Figure One.

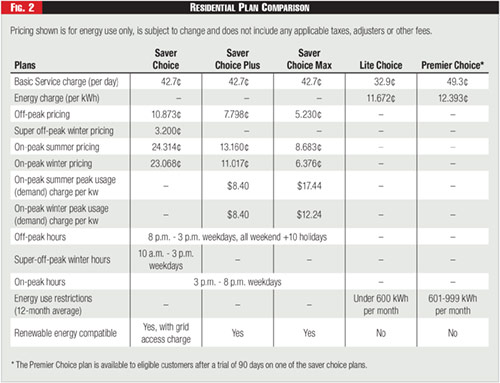

Arizona Public Service was providing five different rate choices to its residential customers. These included two time-of-use energy rates, a time-of-use energy rate with a demand charge, and two flat volumetric rates for smaller customers. More than half had chosen the first three rates.

See Figure Two.

In Maryland, all the utilities were offering a dynamic pricing rebate. California and Michigan were moving all their residential customers to time-of-use energy rates. Fort Collins in Colorado had already moved all its customers to mandatory time-of-use rates.

When he awoke from his Big Dream in 2040, he found a world that was very different from the one described above.

Solar roofs, electric cars, and batteries were everywhere. And millennials were in their forties. Generation Z was in its twenties.

But some things had not changed. Wireless electricity was still waiting to be discovered. It was still the topic du jour in engineering departments at Carnegie Mellon, MIT, and Stanford. The grid was very much there.

At a first glance, it did not differ that much from the grid he had seen in 2020. Transmission towers, substations, circuits, feeders, transformers, and meters all looked generally familiar. But on a closer look he discovered advanced semi-conductors were embedded in all of the elements of the transmission and distribution system that delivered the power to customers. The 2040 Grid was a digital grid with sensors at key locations transmitting reports in real time to the grid managers.

An even bigger change had taken place in the manner in which electricity was being generated. Most of the power flowing through the lines was coming mostly from zero carbon sources in three-quarters of the country, with California, Hawaii, and New York leading the way, with Colorado, Illinois, and Minnesota right behind them.

The air felt good. He thought that the threat of catastrophic climate change had passed or at least been deferred to the long-term future. Al Gore and Jerry Brown, icons of his era, would have been so glad to see this happy end state.

Of course, once he started talking to the system operators at one of the ISOs, he discovered that the power system now had to deal with new challenges. Power supply had become intermittent, as it switched rapidly and unpredictably among wind, solar, hydro, natural gas, and nuclear resources. Electricity prices fluctuated in wholesale markets from second to second, minute to minute. But the system was fully able to cope with that. The lights stayed on and power bills had become affordable.

He wondered why and began talking to homeowners and new developers. And that is where he discovered the biggest change that had taken place. It was not on the supply side of the electricity market but on the demand side.

About half the homes were meeting at least some of their energy needs with solar panels, and about a quarter of the homes had battery storage. One out of ten homes had an electric vehicle in the garage. And just about every major appliance in the home was digital and Wi-Fi enabled.

Instantaneous load flexibility had emerged as the perfect complement to renewable resource intermittency.

Wholesale prices were seamlessly flowing directly to the appliances. Some homeowners, who were interested in lowering their power bills, had programmed their preferences into their smart phones and their Alexa 5.0 devices.

As prices rose, the least important appliance was either turned off or toned down. As prices continued to rise, the next least important appliance was either turned off or toned down. And so on, in a pre-determined loading order of end-use loads.

The opposite happened when prices fell. The homeowners did not have to spend time in front of the phone checking hourly prices. They simply took advantage of getting a lower bill in return for sacrificing some comfort. Each homeowner was able to make the tradeoff between comfort and bill savings at their own pace. All of them had one day programmed their energy lifestyle into Alexa 5.0 devices.

Some homeowners hedged part of their energy purchase decision by buying power on the forward market at a known price and buying the remainder on the spot market. Some hedged it entirely by buying their entire usage on the forward market, essentially having a flat bill.

Rip Van Winkle Jr. concluded that market pricing concepts that were ubiquitous in wholesale markets in 2020 before the onset of his Big Sleep, had become ubiquitous in retail markets two decades later.

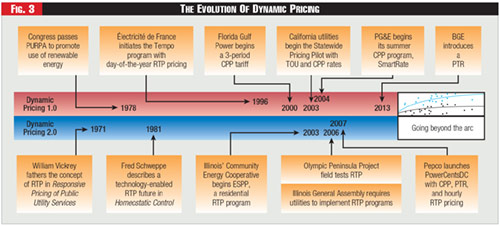

He remembered that MIT's Fred Schweppe had anticipated this phenomenon back in 1978 when he coined the phrase homeostatic control. Around the same time, EPRI's Clark Gellings had articulated a vision of getting prices to devices through technological innovation and propounded the concept of flexible load shapes that no one seemed to understand. Schweppe and Gellings were simply ahead of their time. They were futurists whose dream had come to pass.

Dynamic pricing had evolved.

See Figure Three.

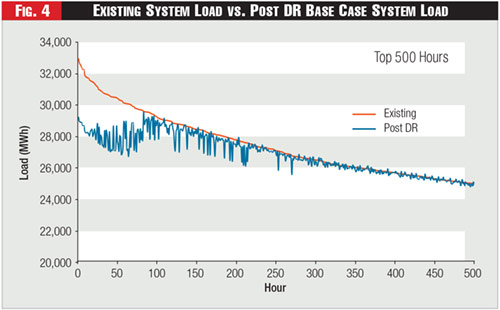

Then he recalled a study for the Empire State that had been carried out a decade prior to the Big Sleep. It was a simulation of what would happen if the state mandated dynamic pricing for all retail transactions across residential, commercial, and industrial classes.

The study had found that system peak load would be decreased by approximately ten percent, eliminating the need to install or retain more than thirty-eight hundred megawatts of generation capacity representing, for example, fifty peaking generation units of seventy-five megawatts each. The load curve was projected to change dramatically, as shown here.

See Figure Four.

The study found that dynamic pricing created value by avoiding the economic inefficiencies associated with flat rates, thus increasing the sum of consumer surplus and producer surplus.

Consumer surplus accounts for changes in costs, but it also accounts for the gain in customer value from increased consumption in most non-critical hours and the loss of customer value associated with reduced consumption in critical hours.

Of course, the changes modeled in the study were computed in a world where decarbonization was not in vogue, a world where advanced metering infrastructure was still in its infancy. Smart phones had not become ubiquitous.

Wi-Fi-enabled appliances did not exist, nor did electric vehicles or rooftop solar mills. The Millennial Generation was in grade school. And anyone talking of wind mills was likely to be dismissed as another Don Quixote charging at wind mills.

In 2040, the world had been transformed. He recalled the utilities in Arizona and Oklahoma that had offered a glimpse of the future before he fell asleep. Their customer-centricity had been emulated by other utilities. And digital technology in customer homes had made the transition painless. The Schweppe-Gellings vision had been actualized.

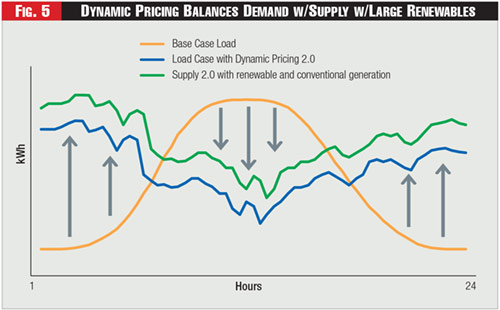

See Figure Five.

The strong light of the morning sun woke him up. This time he was really awake. He had awoken during the night but that was still part of the dream.

It was still 2020. There was a lot of work remaining to be done to actualize the vision he had dreamed about. He packed his belongings, got into his SUV, and drove back to his office. The real work was just starting.

See also: Comments on 2040: A Pricing Odyssey

Lead image © Can Stock Photo / umnola

Category (Actual):

Department:

Clik here to view.