Survey of consumer advocates identifies areas of agreement and disagreement

Ryan Hledik and Ahmad Faruqui are economists with The Brattle Group. Comments can be directed to ryan.hledik@brattle.com. This article is based in part on research conducted for the Edison Electric Institute, which was interested in exploring a range of rate options related to distributed generation. The authors are grateful to EEI staff and Brattle colleagues Josephine Duh, Jurgen Weiss, and Phil Hanser for helpful comments on earlier drafts. The views expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and not those of The Brattle Group or its clients.

Consider industry developments such as growth in the adoption of distributed generation and the arrival of Wi-Fi thermostats, digital appliances and smart meters. Consider also the growing interest in promoting price-based demand response. Both have recently exposed deficiencies in the standard non-dynamic volumetric residential rate offerings of most electric utilities.

One deficiency in particular has persisted for decades. The under-representation of the cost of generating and delivering power during peak times of day has been exacerbated by these developments. Similarly, off-peak costs have been overstated.

As a result, residential rate reform has emerged as a pivotal issue. There is a challenge facing the industry. Flat and largely volumetric rates do not sufficiently reflect time-differentiation in underlying resource costs. Nor do they sufficiently reflect the peak demand-driven nature of infrastructure investments that the rates are intended to recover.

This leads to under-recovery of costs from some customers who use the power grid heavily, or who otherwise rely on it as a form of backup power. Those costs are recovered from other customers who pay more than their fair share of the grid, raising concerns about fairness and equity.

A variation on the existing residential rate design that could address this issue is the introduction of demand charges. They would recover some portion of the utility's costs through a charge based on a measure of the customer's peak demand for electricity (kilowatts) rather than on the customer's total monthly consumption (kilowatt-hours).1

There are potential benefits to this approach. The introduction of well-designed demand charges would help to address the fairness issues described above. They would reduce a cross-subsidy between customers with flat consumption profiles and those with peaky consumption profiles.

Demand charges would also provide customers with an opportunity to reduce their electricity bills. Customers could manage their electricity demand, either through behavioral changes or through the adoption of emerging technologies (such as smart thermostats, automated appliances, energy storage). If the rate is well designed, this should lead to a reduction in system costs for the utility as well.

It is worth recalling that demand charges have been a standard feature of commercial and industrial customers for decades. They provide regulatory precedent for including these rates in future residential offerings.

See the sidebar on the last page: Brief History of Demand Charges.

Many agree that the current residential rate design is unsustainable. But some industry stakeholders have expressed concerns about the introduction of demand charges as the solution. To fix the problems of today's rates, it will be important to develop a consensus-oriented path forward for residential rate design.

This article summarizes perspectives on both sides of the demand charge issue. Based on this review, it proposes practical initiatives to address key concerns about residential demand charges.

The authors believe that well-designed and carefully implemented demand charges have the potential to significantly improve existing rate designs.2

The focus of this article, however, is not on making the case for demand charges. Instead, the focus is on addressing the commonly-voiced concerns of the consumer advocacy community.

The perspectives on demand charges presented in this article, therefore, are an attempt to synthesize the broad range of views on this issue, rather than reflecting only the opinions of the authors.

The industry stakeholders who have been engaging in this issue include consumer advocacy groups, environmental groups, rooftop solar developers, research organizations (such as the national energy research labs), policymakers, regulators. And, of course, the utilities who are proposing the rate changes.

In this article, we have focused on the views of the consumer advocacy community. Expanding the scope to include other stakeholders would be a valuable future research activity.

It is also important to note that this article is focused on views of the general advantages and disadvantages of demand charges, as opposed to specific implementation issues such as how to best design a demand charge.

Competing Perspectives

A path forward for residential rate reform that garners the support of industry stakeholders and regulators will necessarily be preceded by constructive open dialogue on the issue. To this end, we surveyed consumer advocates to identify areas of consensus and disagreement on the merits of demand charges. Specifically, we conducted phone interviews with nine consumer advocates at national and state-level organizations.

Our survey is further informed by participation in more than a dozen industry events. Each addressed residential demand charges over the past two years.

Examples of such industry events includes:

EUCI's Residential Demand Charge Symposium, Denver, Colorado, May 2015. Harvard Electricity Policy Group's 79th Plenary Session, Washington, D.C., June 2015. NARUC's 127th Annual Meeting, Austin, Texas, November 2015. NASUCA's Annual Meeting, Austin, Texas, November 2015.

We also assembled and reviewed a rapidly growing database of media coverage, publications and regulatory filings on demand charges.

We have found that there is significant diversity in familiarity with the concept of residential demand charges. Some have been closely studying the topic and are well acquainted with the details of the rate design. Others have a basic understanding of demand charges based on experience with rates for commercial and industrial customers.

In some cases, there are misconceptions about demand charges.

For instance, demand charges often are confused with fixed monthly customer charges, or with time-varying or dynamic rates. While in some ways demand charges can be conceptually similar to these other rate designs, there are important and distinct differences that may go unrecognized.

Overall, our survey of consumer advocates identified perspectives that ranged from direct opposition to guarded support for residential demand charges. In many cases, the skepticism can be traced to a perceived lack of experience that the residential class has with these rates.

Where there is support for demand charges, it is generally because the rates are viewed as fair and equitable. And because they are perceived to provide an opportunity for customers to reduce their bills through load shifting, energy efficiency, and other means.

While consumer advocacy groups have generally been skeptical of residential demand charges, the concept has not faced universal opposition.3 The environmental community has highlighted the potential benefits of demand charges in some instances. One consumer advocate expressed support for the use of demand charges to recover distribution capacity costs.

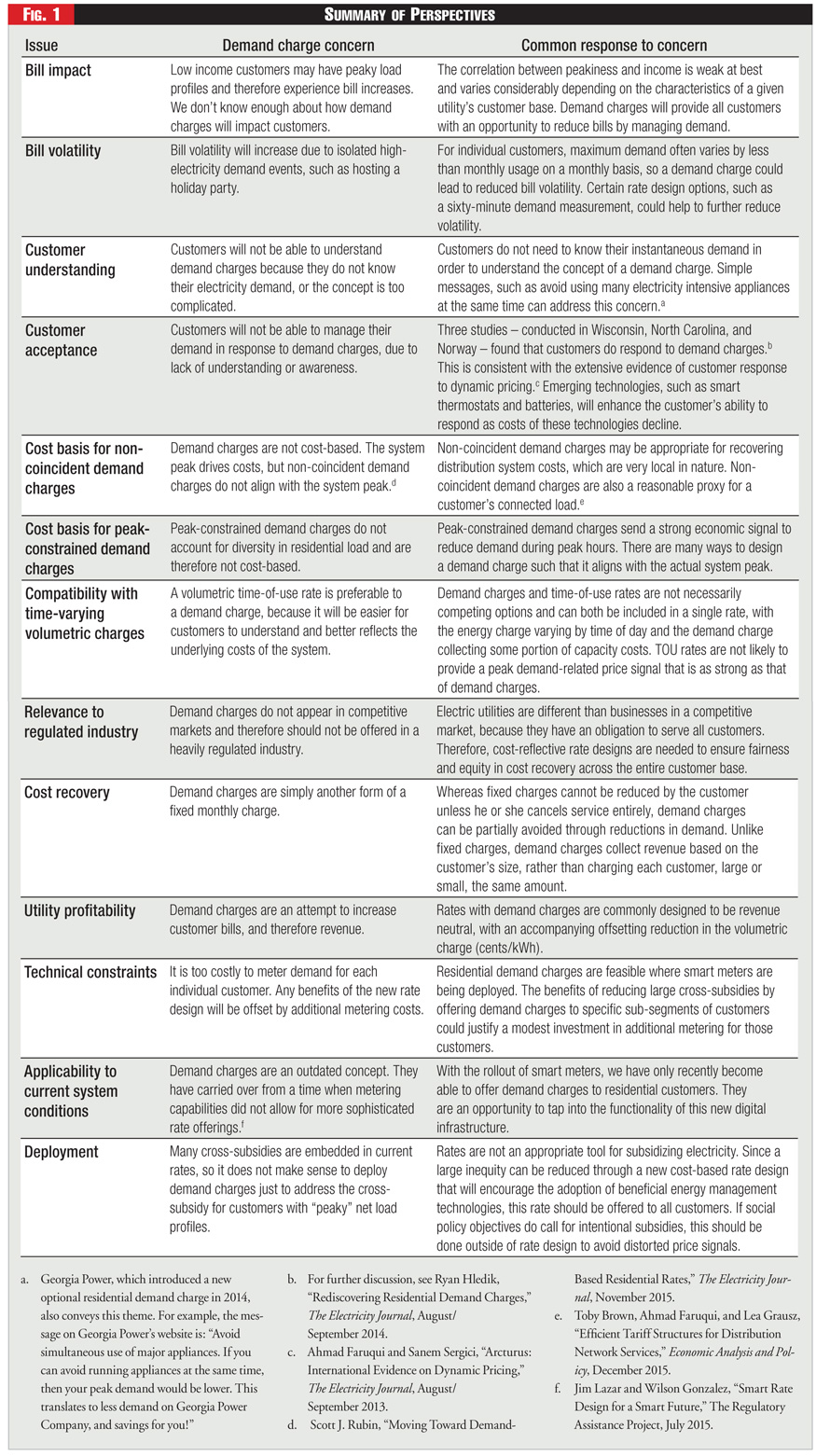

In recognition of the multiple views on demand charges, we have attempted to summarize the perspectives on both sides of each issue. This is intended to help identify the gap where there is disagreement, in order to determine a productive path forward.

The summary is provided in Figure 1. Download Figure 1 in PDF format here.

Bridging the Gap

At times, the electricity industry appears to be at a stalemate when it comes to residential rate reform. The need to improve residential rate design is recognized by many as an urgent issue. But in many cases regulatory decisions about the best way to move forward are being postponed and delayed.

So how does the industry overcome this paralysis? How can we bridge the gap of disagreement and resolve the opposing views?

We propose eight important activities that will help to address key stakeholder concerns. The activities are designed to facilitate a consensus-oriented approach to the transition to demand charges.

Note that each utility has its own is unique history with rate design. Regulatory and policy objectives vary by state, as do the mix and preferences of customers and local stakeholders.

Therefore, we recommend that utilities tailor these suggestions to their own unique circumstances. These ideas should be considered a menu of options from which utilities can pick and choose, rather than a sequential checklist of activities.

Further, it is not necessary that these activities delay the rollout of demand charges. Several of the activities can be conducted in parallel to the demand charge rollout, as part of ongoing efforts to help customers understand and manage their electricity bills. A "test, learn, and adapt" approach would allow full-scale deployments to be rapidly refined and improved over time.

1. Quantify bill impacts, particularly for low and moderate income customers.

Detailed bill impact analysis will identify the customers whose bills increase or decrease on the new rates. This analysis is also helpful in determining other important but sometimes overlooked factors, such as month-to-month bill volatility. New data from smart meters and big data market research firms can be combined to conduct this distributional analysis across sociodemographic customer groups at a level of detail that was not possible until recently.

2. Assess customer under-standing of demand charges through market research.

Research such as focus groups and surveys can be used to test customer acceptance of demand charges. Through survey-based conjoint analysis, the relative attractiveness of different demand charge designs could be measured.

3. Assess customer response to demand charges through empirical analysis.

If customers are able to shift load away from high load hours, they will reduce their bills. Well-designed pilots would offer the advantage of testing demand charges in a live but controlled setting.

4. Establish a national conversation on residential demand charges.

Given the emerging industry interest in this topic and the number of states that are currently reforming residential rates, an organized forum could be established and include facilitated discussions on key issues such as those identified in this article. Participants should include utilities, regulators, and stakeholders.

5. Consider innovative variations on conventional demand charge designs.

Demand charges are typically thought of as either non-coincident, where demand is measured as the maximum at any point in the billing cycle, or as peak-constrained, which typically means that demand is measured only during a window of peak hours of the day during the billing cycle. But there are many other less common variations to be considered.

6. Develop a customer education plan.

At each step in the rate design process, decisions about how to design the rate can be tied back to their implications for customer communications. Linking the two activities in this way will improve the likelihood that the rate is designed to be acceptable to customers.

7. Phase in the rate gradually.

Gradualism is a principle of ratemaking that is sometimes emphasized in regulatory proceedings. Phasing in a demand charge over time will help to reduce the bill impact that would otherwise be experienced by customers. And it will give them time to adjust to the new rate structure. There are several options available for making this gradual transition without excessively delaying the rollout.

8. Consider protections for vulnerable customers.

With any rate transition, there is often a policy focus on ensuring that vulnerable customers are not burdened with large bill increases. Many customer protection mechanisms are possible, such as a rate carve-out for very small consumers of electricity.

Conclusions

Ratemaking strategies must be robust. They must be flexible enough to respond to evolving policy goals and changes in the power system and in the customer base.

For example, declining block rates were popular early in the power industry's history. This was when average costs exceeded marginal costs. Growth in electricity consumption would lead to lower rates.

This changed when the industry matured and average costs decreased. Policy focus shifted toward encouraging conservation. Inclining block rates became popular as a result.

More recently, smart meters have been widely deployed. Time-varying and dynamic rates have received increasing attention.

Now, there are emerging concerns about equity and fairness in rate design, particularly as it relates to effects of growing adoption of distributed generation. Rate designs must continue to evolve.

Residential demand charges have shown promise as a potential solution to this issue. But transitioning to this new rate structure will require close coordination with industry stakeholders who present a broad range of perspectives on the topic. An approach to rate reform that is based on primary research, proactive outreach and pragmatic transition planning will greatly improve the effectiveness of the transition.

Sidebar: Brief History of Demand Charges

1881: Thomas Edison's first contract for electricity is a charge per lamp installed.

1892: British engineer John Hopkinson differentiates fixed and variable costs but continues to define maximum demand as total connected load. This two-part rate is promoted in the U.S. by Samuel Insull.

Mid-1890s: Controversy over price discrimination in special contracts leads to a search for consistent pricing scheme. Arthur Wright introduces demand charges based on maximum actual demand, while William Barstow proposes to measure demand coincident with the system peak.

Early to mid-20th century: Electrification of the U.S. Demand charges persist for commercial and industrial customers, but billing at the household level is mostly through volumetric rates due to metering constraints.

Middle to late-20th century: A period of relatively little change in residential rate design.

1970s and 1980s: Pilot studies assess the effectiveness of residential time-of-use pricing. Demand charges are often a component of these rates. The Public Utility Regulatory Policies Act of 1978 requires time-of-use rates. But residential demand charges are largely lost in the mix.

Early 21st century: The rediscovery of residential demand charges. Advancements in metering technology remove a technical barrier to offering demand charges and time-varying rates to the mass market. Concerns about equity in an environment of growing adoption of distributed generation lead utilities to file proposals to reform residential rates. Many of these proposals include a demand charge.

Endnotes:

1. A demand charge is not based on a truly instantaneous measure of demand, as it is typically averaged over an interval of fifteen, thirty, or sixty minutes. Further, there are a variety of ways in which demand could be defined for the purposes of billing a demand charge (such as maximum demand during a period that is coincident with the system peak, maximum during a period that is coincident with the class peak, or maximum demand based on the customer's own peak over the course of the month). Other alternatives are also possible.

2. See Ahmad Faruqui and Wade Davis, with Josephine Duh and Chris Warner, "Curating the future of rate design for residential customers,"Electricity Policy, July 18, 2016, and Ryan Hledik, "Rediscovering Residential Demand Charges,"The Electricity Journal, 27(2), 2014.

3. For instance, the Rocky Mountain Institute acknowledged the opportunities that demand charges provide for automated demand response in its report "The Economics of Demand Flexibility," and identified residential demand charges as one option for introducing greater sophistication into retail rates in "Rate Design for the Distribution Edge." The Clean Energy Group and the National Renewable Energy Laboratory have both highlighted the potential synergies between demand charges and behind-the-meter energy storage in recent publications.

Category (Actual):